Surveiller le littoral de l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard

– L’équipe du laboratoire climatique de l’UPEI est dirigée par Adam Fenech et composée de Xander Wang, Don Jardine, Ross Dwyer, Andy MacDonald, Luke Meloche et Catherine Kennedy –

L’érosion côtière est le principal défi que le changement climatique pose à l’Île-du-PrinceÉdouard en raison des ondes de tempête, de l’élévation du niveau de la mer et des niveaux d’eau élevés. Les fragiles rivages de sable et de grès de l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard subissent souvent l’usure de l’eau, des vagues, de la glace et du vent. On a mesuré que l’élévation du niveau de la mer à Charlottetown, à l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard, a augmenté de 36 centimètres au cours du dernier siècle (1911-2011 d’après Daigle, 2012), et on prévoit qu’elle augmentera encore de 100 centimètres au cours des 100 prochaines années (GIEC, 2021). En ce qui concerne les tempêtes dommageables, le Groupe d’experts intergouvernemental sur l’évolution du climat (GIEC), l’autorité scientifique de la communauté mondiale en matière de climat, a conclu qu’il était « pratiquement certain » qu’il y avait eu une hausse de l’activité intense des cyclones tropicaux dans l’Atlantique Nord depuis les années 1970; et « plus probable qu’improbable » que ces cyclones tropicaux intenses augmenteraient dans l’Atlantique Nord à la fin du XXIe siècle (GIEC, 2013). En raison de ces changements océaniques, géologiques et de tempêtes prévus, l’érosion côtière devrait se poursuivre et probablement s’aggraver, menaçant les infrastructures publiques et privées et entraînant un coût économique important pour les 1 260 kilomètres de littoral de l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard (ACZISC, 2005).

L’étude la plus récente examinant les taux d’érosion côtière pour chaque mètre de côte de l’Îledu-Prince-Édouard (Webster et Brydon, 2012) en interprétant des photographies aériennes du littoral de l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard pour les années 1968 et 2010 au moyen de techniques d’orthorectification et de délimitation du littoral a calculé un taux d’érosion côtière annuel de 0,28 mètre par an.

Une évaluation quantitative des risques pour les résidences côtières (maisons, chalets), les infrastructures de sûreté et de sécurité (routes, ponts, usines de traitement des eaux, hôpitaux, services d’incendie, etc.) et le patrimoine (églises, cimetières, phares, sites archéologiques, parcs, etc.) a été réalisée par le Climate Lab de l’UPEI afin de déterminer quelles infrastructures de l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard sont menacées par l’érosion côtière. Il en ressort que plus de 1 000 résidences (maisons et chalets), plus de 40 garages, 8 granges et près de 450 dépendances sont vulnérables à l’érosion côtière. Même 17 phares, ces icônes de la culture maritime, ont été jugés à risque. Ces résultats scientifiques étaient importants, mais ils risquaient de se retrouver sur une étagère dans un rapport scientifique s’ils n’étaient pas suffisamment communiqués aux organisations et aux communautés de l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard. Mais comment faire au mieux?

Environnement de visualisation des impacts de la côte (CLIVE)

CLIVE est une interface géovisuelle qui combine les données côtières disponibles, les enregistrements historiques et les prévisions de changement climatique, et les traduit en un outil d’information géovisuel tridimensionnel permettant aux utilisateurs de « voler » au-dessusde l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard, en faisant monter et descendre le niveau de la mer et en cliquant sur les taux d’érosion côtière. Programmé dans le partagiciel UNITY, CLIVE combine des données provenant d’une vaste archive provinciale de photographies aériennes documentant l’érosion du littoral aussi loin historiquement que 1968, et les dernières données numériques d’ élévation à haute résolution dérivées de levés laser connus sous le nom de LiDAR, une technologie de télédétection qui mesure la distance en illuminant une cible avec un laser et en analysant la lumière réfléchie.

Une tournée d’engagement public dans seize villes de l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard a été organisée en 2014 et 2018, chaque séance présentant une introduction à la vulnérabilité de l’Île-du-Prince -Édouard à l’érosion côtière et à l’élévation du niveau de la mer, présentant CLIVE, examinant la vulnérabilité des communautés locales et répondant aux questions. Chaque séance était également précédée et conclue par un sondage écrit visant à évaluer les connaissances des participants, leurs préoccupations et leur volonté de s’adapter à l’érosion côtière et à l’élévation du niveau de la mer. L’inquiétude de chaque participant concernant l’érosion côtière était élevée et, dans la plupart des cas, elle a augmenté après avoir été présentée à CLIVE. Plus important encore, ces séances ont motivé les propriétaires de maisons ou de chalets côtiers à réagir à leur vulnérabilité en augmentant leur résilience à l’élévation prévue du niveau de la mer et à l’érosion côtière.

CLIVE a attiré l’attention à l’échelle nationale et internationale, y compris le journalisme de texte national du Globe and Mail (19 février 2014), la couverture de diffusion nationale canadienne de la Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (World Report Radio le 11 février 2014), la couverture de journal international (National Geographic, 16 décembre 2015) et la couverture de télévision internationale des médias Al Jazeera. CLIVE a remporté en 2014 un prix international décerné par le Massachusetts Institute of Technology pour la communication sur les risques et la résilience des côtes. La technologie CLIVE a été exportée vers la ville de Los Angeles, et mise en œuvre dans plusieurs comtés de la Nouvelle-Écosse et du Nouveau-Brunswick, ainsi qu’à travers le Canada.

Cette sensibilisation accrue aux problèmes côtiers a incité le gouvernement de l’Île-du-PrinceÉdouard à soutenir le Climate Lab de l’Université de l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard dans la mise en place d’un système de surveillance côtière servant de système d’alerte précoce pour l’érosion côtière. Ce système comprend des mesures à la ligne de piquetage, des relevés par drone, des marégraphes et des stations climatiques.

– UPEI Climate Lab team led by Dr. Adam Fenech, and including Dr. Xander Wang, Don Jardine, Ross Dwyer, Andy MacDonald, Luke Meloche, and Catherine Kennedy –

Coastal erosion is the primary challenge that climate change presents to Prince Edward Island through storm surges, sea level rise, and high water levels. The sensitive sand and sandstone shorelines across Prince Edward Island often experience a wearing away by water, waves, ice, and wind. Sea level rise measured at Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island has increased by 36 centimetres over the past century (1911-2011 from Daigle, 2012) and is anticipated to increase by a further 100 centimetres over the next 100 years (IPCC, 2021). In terms of damaging storms, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the global community’s scientific authority on climate matters, concluded that they were “virtually certain” that there had been an increase in intense tropical cyclone activity in the North Atlantic since the 1970s, and “more likely than not,” these intense tropical cyclones would increase in the North Atlantic in the late 21st Century (IPCC, 2013). As a result of these anticipated ocean, geological, and storm changes, coastal erosion is expected to continue and likely become more severe, threatening public and private infrastructure at great economic cost to the 1,260 kilometres of coastline on Prince Edward (ACZISC, 2005).

The most recent study examining the rates of coastal erosion for every metre of coastline on Prince Edward Island (Webster and Brydon, 2012) by interpreting aerial photographs of Prince Edward Island’s coastline for the years 1968 and 2010 using orthorectification and coastline delineation techniques calculated an annual coastal erosion rate of 0.28 metres per year.

A quantitative risk assessment of coastal residences (homes, cottages), safety and security infrastructure (roads, bridges, water treatment plants, hospitals, fire departments, etc.) and heritage (churches, graveyards, lighthouses, archaeological sites, parks, etc.) was conducted by the UPEI Climate Lab to determine what Prince Edward Island infrastructure is at risk to coastal erosion, concluding that over 1000 residences (houses and cottages), over 40 garages, 8 barns, and almost 450 outbuildings are vulnerable to coastal erosion. Even 17 lighthouses, those maritime cultural icons, were deemed to be at risk. Such scientific results were significant but were threatened to sit on a shelf in a scientific report unless communicated sufficiently to the organizations and communities of Prince Edward Island. But how best to do this?

CoastaL Impacts Visualization Environment (CLIVE)

CLIVE is a geovisual interface that combines available coastal data, historical records, and climate change predictions, and translates them into a 3-Dimensional geovisual information tool allowing users to “fly” over Prince Edward Island, raising and lowering sea levels and clicking on and off coastal erosion rates. Programmed in the UNITY shareware, CLIVE combines data from an extensive provincewide archive of aerial photographs documenting coastline erosion as far back historically as 1968, and the latest highresolution digital elevation data derived from laser surveys known as LiDAR, a remote sensing technology that measures distance by illuminating a target with a laser and analyzing the reflected light.

A public engagement tour at sixteen towns across Prince Edward Island was held in 2014 and 2018 with each session presenting an introduction to Prince Edward Island’s vulnerability to coastal erosion and sea level rise, introduced CLIVE, examined the vulnerability of local communities and answered questions. Each session was also preceded and concluded with a written survey to gauge attendee’s knowledge, concern and willingness to adapt to coastal erosion and sea level rise. The concern for coastal erosion of each participant was high, and, in most cases, increased after being introduced to CLIVE. Most importantly, these sessions motivated coastal home or cottage owners to respond to their vulnerability by increasing their resilience to the anticipated sea level rise and coastal erosion.

CLIVE has garnered national and international attention including national text journalism from the Globe and Mail (19 February 2014); national Canadian broadcast coverage from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (World Report radio on 11 February 2014), international journal coverage (National Geographic, 16 December 2015) and international television coverage from Al Jazeera media. CLIVE won an international award in 2014 from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for communicating coastal risk and resilience. The CLIVE technology has been exported to the City of Los Angeles, and implemented in several counties in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, as well as across Canada.

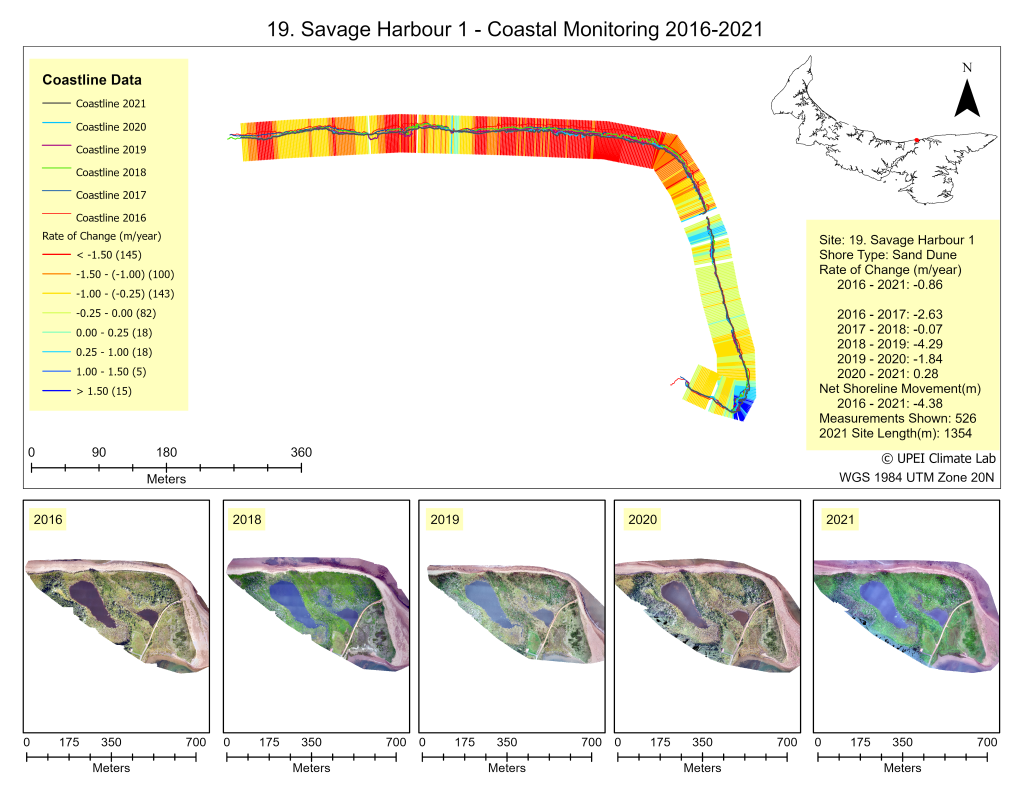

This raised awareness of coastal issues prompted the Prince Edward Island government to support the Climate Lab at the University of Prince Edward Island to build a coastal surveillance system to act as an early warning system for coastal erosion. This system includes peg-line measurements, drone surveys, tidal gauges and climate stations.

Coastal Surveillance System

Every summer, one lucky student working at the Climate Lab at the University of Prince Edward Island has the best job on the Island because they get to visit 200 sites across the province (many with beaches) and take peg-line measurements. This coastline surveillance approach involves physically hammering two 1 metre (m) lengths of 15 millimetre (mm) diameter metal rebar “pins” into the ground in a line spaced 10 m and 20 m roughly normal to the coast; and then manually taking a measurement to the coastal indicator feature (e.g. cliff or bluff edge) using a measuring tape. Metal caps are hammered on the ends of the rebar using a rubber mallet just before the desired depth is achieved (Figure 1). GPS locations of each pin are taken using a Garmin eTrex recreation grade Global Positioning System (GPS) for general site mapping and locating pins year-to-year. Visiting year-to-year provides an early warning system to coastal erosion. Our results show that the average coastal erosion at these pin sites varies year-to-year, but the “usual suspects” show annual erosion rates ranging from 1 to 5 metres. And our preliminary analysis of the coastal impacts from Hurricane Fiona of September 23-24, 2022 show erosion rates at individual locations of over 10 metres.

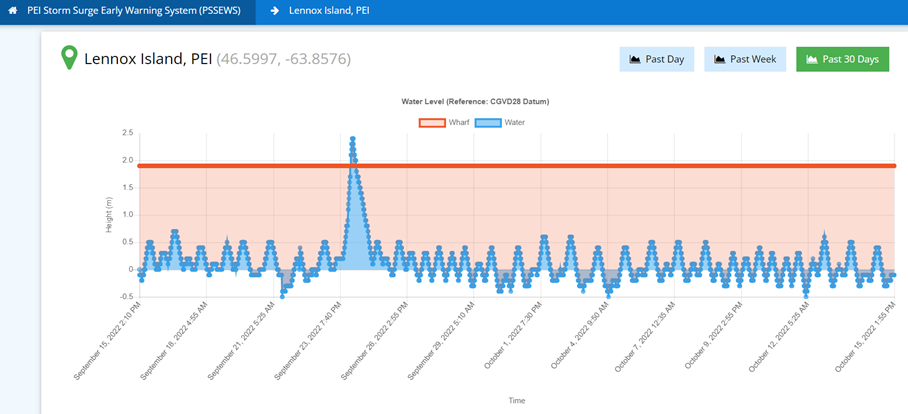

A series of fifteen real-time tidal gauges have been installed across Prince Edward Island by the UPEI Climate Lab, working with the PEI Emergency Management Office and the Mi’kmaq Confederacy of Prince Edward Island. These sites provide the Island’s only direct monitoring for an early warning system of rising tidal levels and storm surges. These tidal gauges were instrumental in alerting PEI ports of the timing and magnitude of storm surges from Hurricane Fiona in September 2022, providing the only record of the actual height of the storm surges (see Figure 4). To complement these coastal stations are a series of inland climate stations installed by the UPEI Climate Lab to measure temperature, precipitation, wind, atmospheric pressure and solar radiation every 2 to 5 minutes, 24/7 at over 70 locations across Prince Edward Island. These stations provide support research on climate vulnerability, impact and adaptation studies across the Island; support the reconstruction of extreme climate events; and support groundtruthing of high-resolution regional climate models. But most importantly, these climate stations provide detailed real-time weather/climate information to Islanders in their day-to-day needs as farmers, fishermen, tourism operators, or simply beach goers.

Final Words

Climate change is presenting greater challenges to Prince Edward Island’s coasts with rising sea levels, storm surges and coastal erosion, but the Climate Lab at the University of Prince Edward Island is keeping watch over Prince Edward Island’s coastlines, measuring them annually with pegs and drones as an early warning system of coastal change. The Climate Lab also installed and maintains a 24/7 surveillance over the Island’s storm surges with 12 tidal gauges, and the Island’s climate with over 70 climate stations, for a real-time early warning system. With such significant vulnerability to anticipated future coastal threats, the UPEI Climate Lab’s climate change early warning systems need to be maintained, and could benefit from financial injections.

Dr. Adam Fenech has worked extensively in the area of climate change for thirty-five years and has edited eight books on climate change. Dr. Fenech is an Associate Professor in the School of Climate Change and Adaptation at the University of Prince Edward Island where he developed the curriculum for the first undergraduate programme in Applied Climate Change and Adaptation. He is presently the Director of the University of Prince Edward Island’s Climate Research Lab that conducts research on the vulnerability, impacts and adaptation to climate change, where his virtual reality depiction of sea level rise has won international awards including one from MIT for communicating coastal science. He maintains the largest fleet of drones at a Canadian university including the largest drone in the country with a four metre wingspan.

adam fenech, andy macdonald, catherine kennedy, Climate Lab de l’Université de l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard, clive, coastal erosion, coastal impacts visualization environment, don jardine, Environnement de visualisation des impacts de la côte, érosion côtière, luke meloche, ross dwyer, xander wang