Planification de l’adaptation : Une approche interdisciplinaire de la réduction des risques liés au changement climatique

– Par Sarah Kehler et S. Jeff Birchall –

Le changement climatique pose un problème complexe et sans précédent. Avec la hausse des températures, le climat mondial devient de plus en plus instable. Les incidences sur le climat, telles que l’élévation du niveau de la mer et la fréquence des phénomènes météorologiques extrêmes, ont de graves répercussions sur les systèmes écologiques et humains. Bien que le changement climatique soit un phénomène mondial, des conséquences uniques et graves se produisent à l’échelle locale. Une érosion côtière incontrôlable, des inondations dévastatrices ou des températures extrêmes atypiques peuvent facilement submerger une communauté non préparée. Les incidences sur le climat risquent d’être coûteuses : en 2025, le Canada devrait subir des pertes de 25 milliards de dollars en raison du changement climatique, et d’ici 2100, les pertes annuelles pourraient atteindre 100 milliards de dollars (Sawyer et coll., 2022). Ces risques soulignent l’importance de l’adaptation, le processus par lequel les communautés anticipent et se préparent au changement climatique.

Les incidences sur le climat locales uniques et qui s’intensifient obligent les communautés à s’adapter. Grâce à leur connaissance du lieu et à leur autorité, les gouvernements locaux, tels que les gouvernements municipaux et régionaux, sont dans une position idéale pour faciliter cette adaptation (Birchall et coll., 2023). La planification urbaine guide la prise de décision à l’échelle locale concernant l’utilisation future des terres, l’aménagement et les infrastructures. La planification de l’adaptation cherche à intégrer la science du climat dans la planification urbaine – une étape essentielle pour se préparer au changement climatique. La prise de décision qui tient compte des projections futures peut considérablement réduire les risques de catastrophe, renforcer la résilience des infrastructures et préparer les communautés à l’incertitude (Davoudi et coll., 2013).

L’adaptation anticipée est un gage de sécurité. L’adaptation atténue les risques de catastrophe et, si un événement se produit, elle peut réduire considérablement les coûts d’intervention et les pertes économiques. En fait, chaque dollar dépensé pour l’adaptation anticipée apportera jusqu’à 15 dollars de bénéfices dans les 75 ans (Sawyer et coll., 2022). Cependant, les avantages de l’adaptation vont au-delà de l’économie. L’adaptation, lorsqu’elle est mise en œuvre de manière équitable, assure la sécurité alimentaire et des moyens de subsistance, améliore la santé et le bien-être des personnes et préserve la biodiversité.

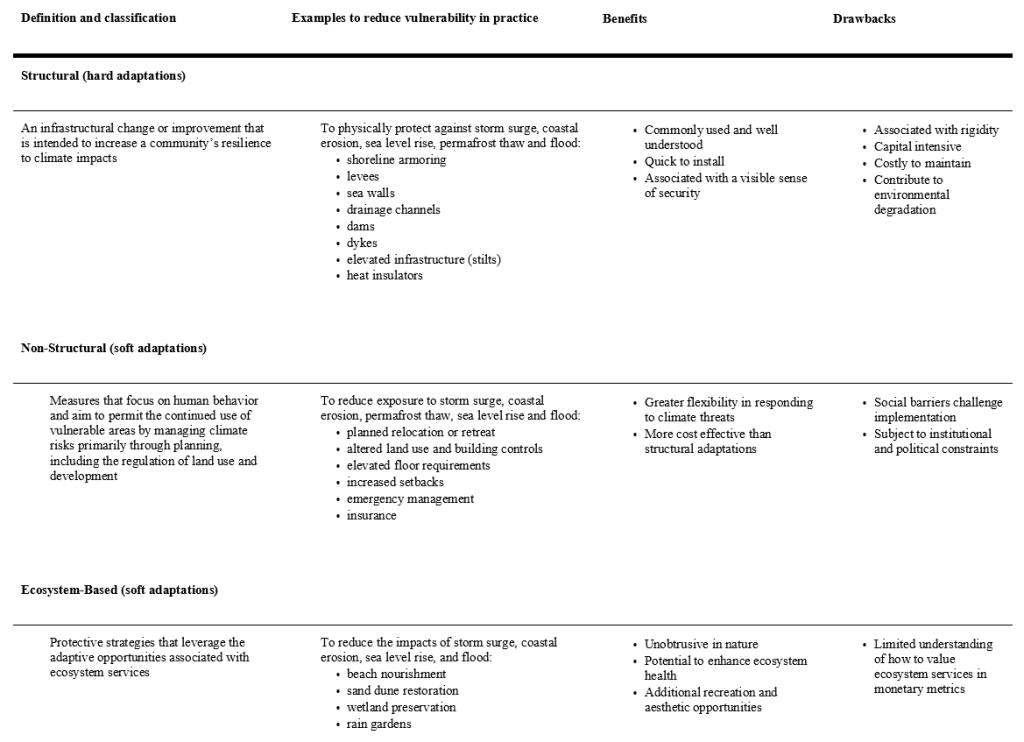

Il existe deux principaux types d’adaptation : la limite stricte de l’adaptation et la limite souple de l’adaptation (tableau 1). La limite stricte de l’adaptation est structurelle et se concentre sur la mise à jour des infrastructures pour qu’elles résistent aux incidences sur le climat. Aujourd’hui, la plupart des adaptations consistent en des mesures d’infrastructures strictes comme les digues (Kehler et Birchall, 2021). Les limites souples de l’adaptation sont non structurelles ou basées sur les écosystèmes, et se concentrent sur la gestion des risques en limitant l’utilisationdes terres et en renforçant les services écosystémiques. Les mesures souples sont de plus en plus reconnues comme des aspects essentiels de l’adaptation; le risque d’inondation, par exemple, peut être atténué par la préservation des zones humides ou des restrictions de zonage.

Pour s’adapter efficacement, il faut une capacité d’adaptation suffisante – les conditions qui permettent aux communautés d’anticiper le changement et d’y répondre (Cinner et coll., 2018). Les gouvernements locaux doivent être flexibles, coopérer entre les administrations et comprendre l’importance de l’adaptation (Birchall et coll., 2023). Elles doivent avoir accès à des ressources, telles que de l’argent, des technologies ou des services, afin d’initier l’adaptation. Le soutien du public, la mobilisation des intervenants et le leadership politique sont à la base de la capacité d’adaptation; sans personnes plaidant pour une action anticipée, l’adaptation a peu de chances de se produire (Ford et King, 2013). Il est de plus en plus évident que la mise en œuvre de l’adaptation est souvent inéquitable, les zones riches recevant un soutien plus important, ce qui diminue la capacité d’adaptation globale de la communauté (Kehler et Birchall, 2021).

L’adaptation n’est pas une panacée pour le changement climatique. Les limites strictes et souples de l’adaptation ont leurs limitations, leurs avantages et leurs inconvénients (tableau 1). Cependant, la dépendance excessive à l’égard de la limite stricte de l’adaptation a mis les communautés en danger : le changement climatique va rapidement dépasser notre capacité d’ adaptation par le biais des seules mesures strictes. Malgré les bonnes intentions, à long terme, la limite stricte de l’adaptation peut entraîner des coûts d’entretien élevés et des risques d’échec, tout en offrant moins d’avantages que la limite souple de l’adaptation (Birchall et coll., 2022). Dans certaines circonstances, les conséquences involontaires des infrastructures coûteuses et des adaptations techniques peuvent conduire à une maladaptation, lorsque les mesures d’adaptation ne diminuent pas les risques et augmentent plutôt la vulnérabilité au changement climatique.

Malheureusement, de nombreuses communautés, dépassées par le coût et l’ampleur des futures demandes d’adaptation, ne bénéficient pas du soutien public et de l’efficacité bureaucratique nécessaires pour y répondre (Birchall et coll., 2023). Ces obstacles peuvent empêcher le processus de planification d’entreprendre une adaptation efficace au niveau local, et augmenter le risque de maladaptation (Kehler et Birchall, 2021). Pour éviter la maladaptation, il faut une adaptation efficace et équitable. Pour ce faire, la planification doit tenir compte des contraintes de capacité d’adaptation et viser à équilibrer les limites strictes et souples de l’adaptation. Ces objectifs peuvent être atteints simultanément. Par exemple, en explorant d’ abord les options souples moins coûteuses et peu perturbatrices, les communautés peuvent éviter les risques de maladaptation, obtenir le soutien du public et conserver des ressources limitées pour le cas où des mesures strictes seraient inévitables.

– By Sarah Kehler, S. Jeff Birchall-

Climate change presents a complex and unprecedented problem. As temperatures rise, the global climate is becoming increasingly unstable. Climate impacts, such as sea level rise and frequent extreme weather events, are causing acute impacts on ecological and human systems. Although climate change is a global phenomenon, unique and severe consequences occur at the local level. Uncontrollable coastal erosion, devastating overland flooding or atypical temperature extremes can easily overwhelm an unprepared community. Climate impacts are likely to be costly: in 2025, Canada is expected to see a loss of $25B due to climate change, and by 2100, annual losses could be as high as $100B (Sawyer et al, 2022). These risks underscore the importance of adaptation, the process through which communities anticipate and prepare for climate change

Unique and intensifying local climate impacts are forcing communities to adapt. With their place-based knowledge and authority, local governments, such as municipal and regional governments, are in an ideal position to facilitate this adaptation (Birchall et al., 2023). Urban planning guides local-level decision making around future land use, development and infrastructure. Adaptation planning seeks to integrate climate science into urban planning – a critical step toward preparing for climate change. Decision making that considers future projections can considerably reduce disaster risk, enhance infrastructure resilience and prepare communities for uncertainty (Davoudi et al., 2013).

Anticipatory adaptation provides security. Adaptation mitigates disaster risk and, should an event occur, can substantially reduce response costs and economic losses. In fact, every $1 spent on anticipatory adaptation will provide up to $15 benefit within 75 years (Sawyer et al, 2022). However, the benefits of adaptation go beyond economics. Adaptation, when implemented equitably, provides food and livelihood security, increases human health and well-being, and conserves biodiversity.

There are two main types of adaptation: hard adaptation and soft adaptation (Table 1). Hard adaptation is structural, focusing on updating infrastructure to withstand climate impacts. Today, most adaptation consists of hard infrastructure measures like sea walls (Kehler & Birchall, 2021). Soft adaptations are non-structural or ecosystem-based, focusing on managing risks through restricting land use and bolstering ecosystem services. Soft measures are increasingly recognized as critical aspects of adaptation; flood risk, for example, can be mitigated through wetland preservation or zoning restrictions.

Adapting effectively requires sufficient adaptive capacity – the conditions that enable communities to anticipate and respond to change (Cinner et al., 2018). Local governments must be flexible, cooperate across jurisdictions, and understand the importance of adaptation (Birchall et al., 2023). They must have access to resources, such as money, technology or services, in order to initiate adaptation. Public support, stakeholder engagement and political leadership underpin adaptive capacity; without people advocating for anticipatory action, adaptation is unlikely to occur (Ford & King, 2013). There is growing awareness that implementation of adaptation is often inequitable, with wealthy areas receiving greater support, decreasing the overall adaptive capacity of the community (Kehler & Birchall, 2021).

Adaptation is not a cure-all for climate change. Both hard and soft adaptations come with limits, benefits and drawbacks (Table 1). However, over-reliance on hard adaptation has put communities at risk: Climate change will quickly outpace our capacity to adapt through hard measures alone. Despite good intentions, over the long-term hard adaptation can carry high maintenance costs and risks of failure, while providing less benefits than soft adaptation (Birchall et al., 2022). In some circumstances, the unintended consequences of expensive infrastructure and engineered adaptations can lead to maladaptation, when adaptation measures do not decrease risk, and rather increase vulnerability to climate change.

Unfortunately, many communities, overwhelmed by the sheer cost and magnitude of future adaptation demands, lack the consistent public support and bureaucratic efficiencies necessary to meet them (Birchall et al., 2023). These barriers can inhibit the planning process from undertaking effective local-level adaptation, and increase the risk of maladaptation (Kehler & Birchall, 2021). Avoiding maladaptation requires effective and equitable adaptation. To do so, planning must address adaptive capacity constraints and aim to balance hard and soft adaptations. These goals can be achieved simultaneously. For example, by exploring less expensive and minimally disruptive soft options first, communities can avoid maladaptation risks, garner public support and conserve limited resources for when hard measures are unavoidable.

Case study: The challenge of adaptation in the Canadian Arctic

While climate change is impacting communities across the globe, the Canadian Arctic currently experiences intensified local-level climate impacts. Recent studies find that, since 1979, arctic amplification has caused northern regions to warm nearly four times faster than the global average (Rantanen et al., 2022). This intense warming has caused substantial physical impacts, such as permafrost thaw, sea ice loss, coastal erosion and biodiversity loss. Isolation, ecological fragility and remoteness further render northern communities vulnerable to climate change.

Extreme exposure to climate impacts require intensive adaptation. However, Arctic communities face unique adaptation barriers and maladaptation risks. Many of these barriers and risks remain unknown due to lack of technical data and personnel, and inadequate public consultation. As climate change worsens, it is becoming apparent that hard and soft adaptations typically used in warmer climates have little utility in the Arctic. Extreme cold narrows ecological niches, reducing biodiversity and constraining the feasibility of ecosystem-based adaptation. Simultaneously hard infrastructure adaptation is limited by structural and ecological fragility, and maladaptation often leads to widespread environmental degradation. As a result, infrastructure maintenance and upgrades are becoming increasingly expensive, which communities struggle to afford due to low property values. When infrastructure goes unmaintained, disaster risk increases and northern communities, which tend to be isolated and reliant on a single economic industry or subsistence food production, are vulnerable to even minor disruptions (Birchall et al., 2022).

For Arctic communities adaptation is complex. Indigenous knowledge systems are crucial to effective adaptation, and may offer insight into current unknowns. However, as mindset barriers and inequality prevent collaboration, high proportions of marginalized groups can restrict effective adaptation (Kehler & Birchall, 2021). Collaboration between Indigenous communities and local governments is necessary to overcome barriers and co-create effective long-term adaptation policies (Birchall & MacDonald, 2019). Adaptation in the Canadian Arctic offers a unique opportunity to address lagging reconciliation and set an example for integrating non-western knowledge systems into disaster risk reduction.

Sarah Kehler is currently a PhD student at the University of Alberta; her general area of study is Urban and Regional Planning. She is currently a research assistant with the Climate Adaptation and Resilience Lab, focusing on barriers to achieving equitable and effective policy for adaptation and resilience to climate change.

S. Jeff Birchall, PhD, RPP, MCIP is an Associate Professor of Local-scale Climate Change Adaptation/ Resilience, in the School of Urban and Regional Planning, Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta, where he serves as Director of the Climate Adaptation and Resilience Lab. Jeff leads the UArctic Thematic Network on Local-scale Planning, Climate Change and Resilience. Further questions regarding the article can be directed to jeff.birchall@ualberta.ca

Changment climatique, jeff birchall, sarah kehler, university of alberta