Les dix événements météorologiques les plus marquants au Canada en 2020

– Par David Phillips –

Cet article a été publié pour la première fois par Environnement et Changement climatique Canada.

Introduction

L’année 2020 en aura été une sous le signe de l’instabilité, alors que le monde a fait face à la plus grande crise de santé publique depuis plus d’un siècle. La pandémie de COVID-19 a certainement fait les manchettes, avec les décès, les dommages économiques et les troubles sociaux ressentis par les milliards de personnes dans le monde. Parfois, la mise en quarantaine et la distanciation sociale ont été plus difficiles en raison des conditions météo. Vers la fin de l’année, au milieu d’une deuxième et d’une troisième vague, les statistiques sur la morbidité liée au virus étaient effrayantes et la fatigue liée à la pandémie a pris le dessus. Cependant, on a espoir que des vaccins efficaces permettront de faire disparaître rapidement cette grave menace. Il n’existe toutefois aucun vaccin contre les phénomènes météorologiques extrêmes, et tout repose sur la planification durable, la préparation et l’intervention rapide.

Partout au Canada, 2020 a été une autre année de conditions météorologiques extrêmes, destructrices et coûteuses. Les dommages matériels causés par la météo coûtent des millions de dollars aux Canadiens, et des milliards de dollars à l’économie. D’après les estimations préliminaires compilées par Catastrophe Indices and Quantification Inc. (CatIQ), il y a eu neuf événements météorologiques catastrophiques majeurs cette année, avec des estimations des pertes assurées totales approchant les 2,5 milliards de dollars. Mais cela ne représente qu’une fraction des pertes matérielles et des coûts d’infrastructure attribuables à des phénomènes météorologiques majeurs et nuisibles qui ont coûté des milliards de dollars de plus.

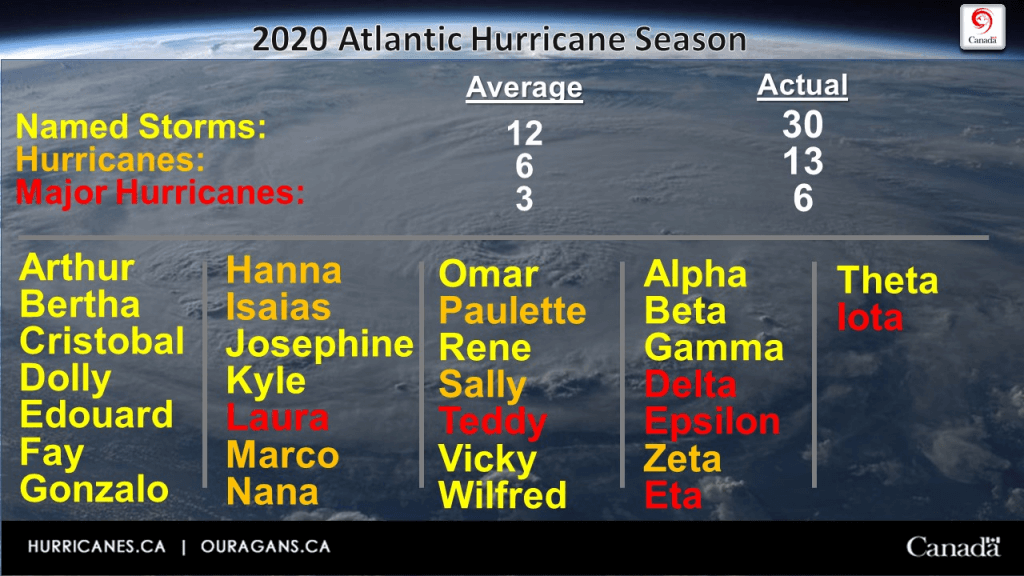

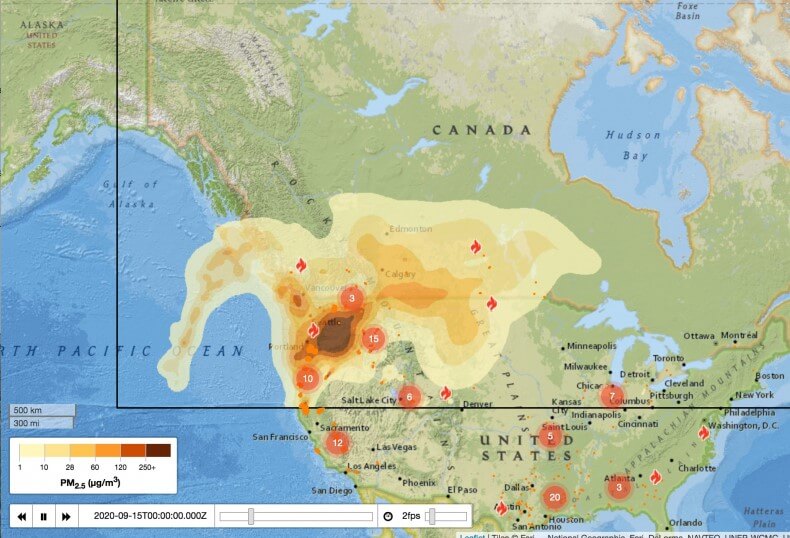

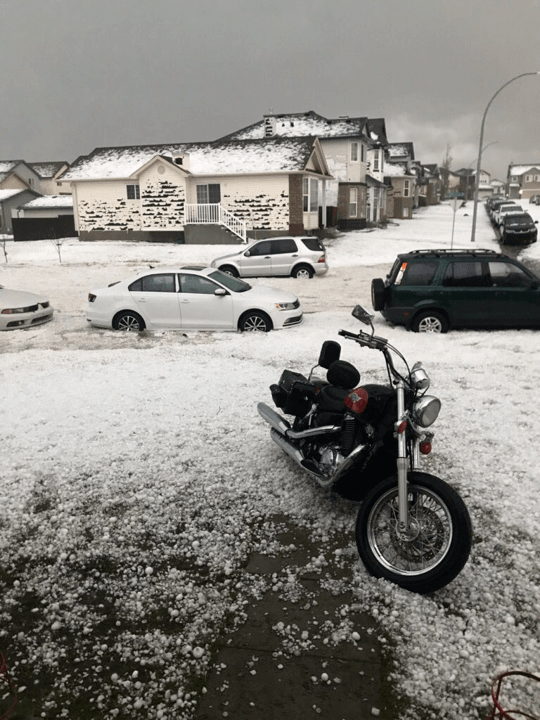

Il est rare que Calgary ne figure pas sur la liste des dix événements météorologiques les plus marquants, et cette année ne fait pas exception. Une tempête de grêle qui a frappé la ville le 13 juin a causé pour un milliard de dollars de dommages, la plaçant ainsi en première position. L’Alberta a enregistré deux des trois événements météorologiques les plus marquants de l’année, avec une deuxième catastrophe météorologique à Fort McMurray, où des rivières engorgées par la glace ont inondé le centre-ville à la fin d’avril. Fait préoccupant, six des dix catastrophes météorologiques les plus coûteuses au Canada se sont produites en Alberta. Les feux de forêt dans l’ensemble du Canada, en particulier en Colombie-Britannique, ont été presque à leur plus bas niveau en termes de superficie brûlée. Cependant, les feux de forêt causés par le climat en Californie et dans le nord-ouest des États-Unis ont propagé de la fumée vers le nord jusqu’en Colombie-Britannique et en Alberta, forçant des millions de personnes à respirer de l’air sale et vicié pendant près de deux semaines en septembre. Les eaux chaudes de l’océan Atlantique, de la mer des Caraïbes et du golfe du Mexique, combinées à une circulation atmosphérique favorable, ont mené à un nombre record de tempêtes nommées (30) dans l’Atlantique Nord. Au Canada, huit tempêtes ont pénétré dans nos eaux, mais les tempêtes meurtrières et dévastatrices du Sud nous ont en grande partie épargnés. Teddy a été la tempête tropicale la plus puissante à toucher le Canada, mais ce n’était ni Dorian ni Juan.

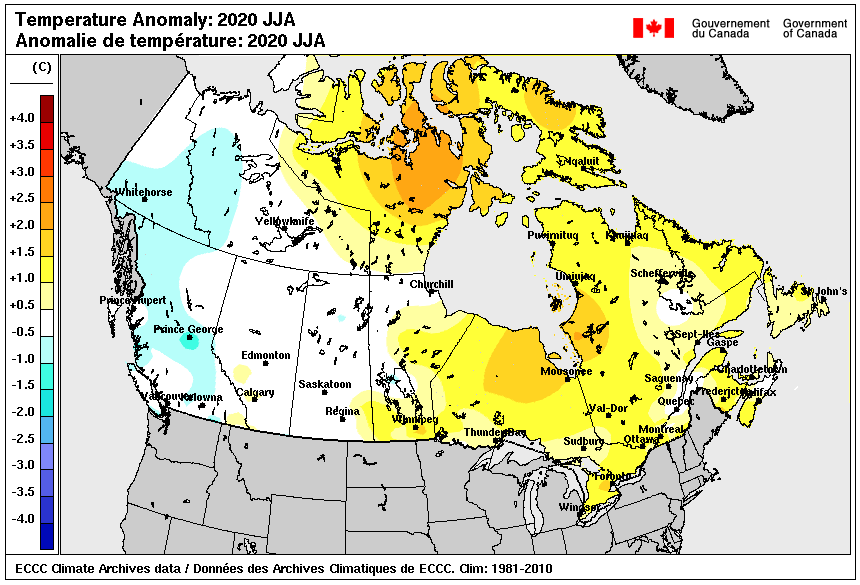

Un dénombrement exact des tornades n’est jamais possible, mais nous nous améliorons au Canada grâce à un suivi et à une surveillance élargis. À l’échelle nationale, 77 tornades ont été enregistrées, dont un possible record de 42 en Ontario. La tornade la plus puissante au Canada s’est toutefois produite à Scarth, au Manitoba, le 7 août. Le printemps a été en grande partie absent dans certaines régions du sud du Canada, mais lorsque l’été est arrivé, il s’est prolongé en force de la longue fin de semaine de mai jusqu’à la fête du Travail. Dans l’est du Canada, la saison s’est avérée être entre le quatrième et le septième été le plus chaud en 73 ans, s’inscrivant dans une vague de chaleur mondiale qui s’étendait de la Sibérie en Russie à la vallée de la Mort aux États-Unis. L’été n’avait pas dit son dernier mot dans l’Est en septembre. En novembre, un long et chaud interlude a duré plus d’une semaine, au cours de laquelle des centaines de records de températures élevées ont été battus et souvent fracassés. Parallèlement, un hiver précoce avec des températures froides et de la neige prévalait dans l’ouest du Canada et dans le Nord. À Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador, l’année a été marquée par une avalanche de neige, avec des chutes record, en janvier à St. John’s et en novembre à Happy Valley-Goose Bay. À St. John’s, le 17 janvier, une tempête monstre a incité les responsables à faire appel aux Forces armées canadiennes. À mi-chemin de l’été, en août, les tempêtes ont assombri la longue fin de semaine du Congé civique, tant à l’est qu’à l’ouest, lorsque de puissantes cellules orageuses ont causé d’importants dommages matériels et des pannes d’électricité, coûtant plus de 50 millions de dollars aux assureurs en Alberta seulement.

Les dix événements météo les plus marquants au Canada en 2020 ont été choisis parmi une liste de 100 événements météorologiques importants et classés en fonction de divers facteurs, notamment leurs répercussions sur le Canada et sa population, l’ampleur de la zone touchée, leurs effets économiques et environnementaux, ainsi que leur durée.

Canada’s Top 10 Weather Stories of 2020

– Par David Phillips –

Prologue 2020

Canada is warming at nearly twice the global rate with parts of western and northern Canada warming three or four times the global average. Sea ice in the North is thinning and shrinking, and our unique ice shelves are crumbling into pieces. While Canada is still the snowiest country, less snow is falling across the south. White Christmases’ are less frequent and less white. Frost-free days are increasing, and our growing season is longer, but so too is the length and severity of the wildfire season. Weather systems are moving slower, leaving more time to make an impact. When it rains it often rains harder and longer. Records continue to topple like never before, often dramatically shattering previous records. So-called unprecedented events are becoming common, happening back-to-back, not decades apart. Our “Goldilocks” weather is not so sure any more with conditions being either too hot or too cold and too wet or too dry.

Scientists have made a clear link between climate change and extreme weather events that include heat waves, wildfires, some flooding and sea ice loss, and strong possibilities for linkages to heavy rain, icing, drought and storminess. As Canadians continue to experience more extreme weather, these top news events will simply, decades from now, be called “normal”. As the Top Ten Weather Stories of 2020 bear out, exceptional weather which we thought was futuristic is occurring here and now. It is playing out in our backyards, in our communities and in our country. What 2020 showed, through smoky skies in British Columbia, frequent hurricanes in the East, and vanishing ice in the North, climate change occurring elsewhere outside of Canada is also having an increasingly greater impact on the health and well-being of Canadians at home.

Introduction

What an unsettling 2020 it was, as the world faced the largest public health crisis in over a century. The COVID-19 pandemic was certainly the top-news story with the lives lost, economic damage and societal unrest felt by the world’s billions. At times, the need to quarantine and social distance was made more challenging owing to the weather. Towards the end of the year in the midst of a second and third wave, the virus morbidity statistics were horrific and pandemic fatigue was taking over. However, there was hope that effective vaccines would soon make the dire threat go away. There is no vaccine for extreme weather only sustainable planning, preparedness and a rapid response.

Across Canada, 2020 was another year of destructive and impactful weather. Property damage from weather cost Canadians millions of dollars and the economy billions. Based on preliminary estimates compiled by Catastrophe Indices and Quantification Inc. (CatIQ), there were nine major catastrophic weather events, with total insured loss estimates approaching $2.5 billion. But that was only a fraction of total property losses and infrastructure costs from major and nuisance weather costing billions more.

Calgary rarely misses a ranking on the top ten weather list and this year it was again Number 1 from a billion-dollar hailer that pummelled the city on June 13. Alberta captured two of the year’s three top weather events with a second disaster in Fort McMurray when ice-choked rivers flooded downtown at the end of April. Of concern, six of the ten most expensive recent weather disasters in Canada have occurred in Alberta. Wildfires across Canada, especially in British Columbia were near-record low in terms of area burned. However, climate-induced wildfires in California and the United States Northwest spread smoke northward into British Columbia and Alberta forcing millions to gasp through foul, dirty air for nearly two terrible weeks in September. Warm waters in the Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico along with a favourable atmospheric circulation led to a record number of named storms (30) in the North Atlantic. In Canada, eight storms entered our response waters but the deadly and crippling storms in the south largely spared us. Teddy was the most powerful tropical storm to affect Canada, but it was no Dorian or Juan.

An accurate count of tornadoes is never possible anywhere, but we are getting better in Canada with more extensive monitoring and surveillance. Nationally, 77 tornadoes were documented including a potential record 42 in Ontario, although Canada’s most powerful twister occurred at Scarth, Manitoba on August 7. Spring was largely a no-show in parts of southern Canada, but when summer did come, it was the summer of summers from Victoria Day to Labour Day. In Eastern Canada, it was one of between the fourth and seventh the warmest summers in 73 years, part of a global heatwave that stretched from Siberia in Russia to Death Valley in the United States. Summer wasn’t finished with the East in September. A lengthy and much welcomed warm interlude occurred in November and lasted more than a week when hundreds of high-temperature records were broken and often smashed. At the same time, an early winter with cold temperatures and snow prevailed across western Canada and the North. For Newfoundland and Labrador, it was snowpocalypse with record-breaking snowfalls in January in St. John’s and in November in Happy Valley-Goose Bay. In St. John’s on January 17, it was a true “Snowmageddon” lockdown prompting officials to call in the Canadian Armed Forces. At summer’s halfway point in August, stormy weather marred the civic long weekend in both east and west when powerful supercell storms inflicted extensive property damages and power outages, costing insurers over $50 million in Alberta alone.

From a list of 100 significant weather happenings across Canada in 2020, events were ranked from one to ten based on factors that included the degree to which Canada and Canadians were impacted, the extent of the area affected, economic and environmental effects and the event’s longevity as a top news story.

Top ten weather events in 2020 countdown

10. August long-weekend storms: East and West

The civic long weekend in August featured some nasty summer weather in both southern Alberta/Saskatchewan and in Ontario. First, in the East, a low-pressure system crossed through central Ontario late August 1 through August 2. The warm front associated with the system brought significant tropical-sourced moisture between 50 and 70 mm from Windsor to the Greater Toronto Area and Niagara, and along the north shore of Lake Ontario. Rainfall in Barrie totalled between 80 and 90 mm, more than the average monthly total, and the highest of any August one-day rainfall in history and the most one-day amount for any month in 25 years. A couple of volunteer observers reported in excess of 100 mm of rain in Western Ontario. The storm system spawned four tornadoes with winds clocking between 130 and 190 km/h. A weather chaser spotted a weak tornado north of Mitchell. In Camden East, strong tornadic and straight-line winds uprooted dozens of trees, some century-old, or broke them off at mid-trunk. In addition, winds lifted shingles from roofs, cracked windows and felled hydro lines and poles. The roof of the Camden East municipal building was torn off and several streets were fully blocked by downed trees. Another tornado touched down in Kinmount near Peterborough where estimated winds approached 190 km/h.

In the West on August 2 and 3, pulses of energy in the midst of hot and humid air destabilized the atmosphere, resulting in several robust storms, featuring large tennis- and baseball-sized pulverizing hailstones. Strong thunder cells also produced damaging wind gusts and heavy rainfall that triggered localized flash flooding. Large hailstones inflicted extensive property damage in Crossfield, Alberta near Carbon, from Cremona to Drumheller, and at a campground northwest of Calgary. Winds in excess of 100 km/h inflicted damage to trees and dwellings in Killam, southeast of Edmonton and at Forestburg. In Macklin, Saskatchewan storm winds took down trees and power lines and tore off a hotel roof. Hail cracked several windows and windshields, damaged siding on several buildings in town and scarred golf course greens. Costs of this August hailstorm in Alberta and Saskatchewan included 4,000 insurance claims totalling $55 million in property losses. Amidst the storm, three non-damaging tornadoes occurred including one at Youngstown and two near Dorothy, Alberta.

9. Fall in Canada – winter in the West and summer in the East

Across much of the Prairies residents welcomed unseasonably warm weather during the first week of November, but with an eye on a powerful storm lining up to the West. From November 7 to 9, the summery interlude came to a dramatic end with the arrival of a slow-moving, moisture-laden Colorado low from the American northwest. Strong winds with gusts up to 85 km/h ushered in the storm and combined with falling temperatures to produce wind chill values of -22. Moreover, the storm featured a mixture of heavy snow and rain and/or a congealment of ice pellets and freezing rain, prompting lockdown conditions from southwestern Alberta (south of Calgary) through central and southern Saskatchewan, and into northwestern Manitoba. It was mostly snow in Alberta and central Saskatchewan with record-breaking amounts drifting and blowing about in sudden whiteout conditions. Saskatoon, Prince Albert and Kindersley, Saskatchewan took the biggest hit with 50 hours of snowfall (30 to 47 cm), much of it blowing around. Maple Creek and Swift Current, Saskatchewan were buried in 2-metre drifts. In southeastern Saskatchewan and in southern Manitoba prolonged periods of freezing rain and ice pellets kept snowfall totals down but added to the treacherous driving conditions. Residents were prepared for the well-publicized winter blast, but, the wintery nightmare created significant impacts with damage to leafed trees and power lines. Travel was nearly impossible and dangerous with suddenly reduced visibility. New snows made most surfaces icy and slippery. Local businesses, community centres and schools closed early or never opened at the beginning of the week as dense snow-choked streets and highways.

In contrast, at the end of October and in early November, southern parts of Ontario and Quebec had a taste of winter with the season’s first snowfall and biting frosts. But summer weather made a quick return with an unprecedented long stretch of record-breaking high temperatures across Ontario, parts of southern Quebec, and eventually into Atlantic Canada beyond Remembrance Day. Over a remarkable stretch of eight days, 200 daily high-temperature records were set from Ontario to Newfoundland with some readings eclipsing the previous record by several degrees. The November “heatwave” also followed a cooler than normal September and October with no 30°C readings, which made it even more special. Persistent southwesterly winds were delivered by the push from a Bermuda High positioned further north and west over the northeastern United States and the pull from the jet stream located along a line between Hudson Bay and central Labrador much further north than would normally be the case. From shovels to golf clubs, the extraordinary warmth had no adverse economic impacts. The gorgeous weekend of November 7 and 8 was aglow in the sunshine, with record warmth and completely dry. Undoubtedly, the best “summer” weekend in the East this year occurred in November. It was an atmospheric gift at a time of the year when temperatures typically hover near freezing, skies are overcast and gloomy, and there are more wet days than dry ones. On November 9, the temperature in Collingwood, Ontario soared to 26°C — one of the highest temperatures ever in the province for November and the warmest November day in 60 years. Even more remarkable than the record warmth was the long stretch of nice days, not a one- or two-day wonder, but lasting a week or more. Temperatures were reminiscent of the middle to late September or what Atlanta Georgia would experience in mid-November. And when it came to an eventual end, it was a gradual downward trend not the dramatic way it began. Among the records set in such places as Windsor, Toronto, Ottawa and Montréal and several other locations were: multiple mean daily maximum and minimum temperature records; the warmest November day ever; latest date in the year when the temperature topped 20°C or more; and the longest consecutive stretch of days above 15°C so late in the year. For some hopefuls in the East, it could only mean that winter would be a week shorter than expected.

8. Frigid spring helps Canadians self-isolate

It is often said that spring is reluctant to arrive in Canada. In 2020, spring was not late; it went missing. Following a mild winter, the weather turned cold across most of southern Canada in March and persisted for another two months. At times, negative temperature anomalies were extraordinary, reaching as much as -22 degrees in parts of Alberta at the end of March. Most of the blame goes to the polar vortex which for most of the winter remained at home, circulating the North Pole before sagging southward in March bringing with it an expansive cold air mass. More than 80% of Canada had a colder-than-normal spring. April was especially cold and cruel being the sixth coldest April in 73 years in the Prairies and southeastern Canada. April felt like late-November with double-digit negative highs and wind chills pushing –35 in central Alberta. The cold spell continued into the first half of May. Temperatures felt more like early March than early May, and Mother’s Day more like St. Patrick’s Day. May days featured single-digits highs and below-freezing lows, and measurable snow. Temperatures in Winnipeg dipped to a low of -10.3°C on May 11 breaking the previous minimum record of -6.2°C in 1996. Moreover, it was the coldest moment post-May 11 ever since records began in 1878. Ottawa set new record daily low minimum and maximum temperatures on several days at the beginning of May. On May 12, it was -4.6°C shattering the record minimum for the day by 3 degrees and the coldest ever post-May 12 at the airport. May snowfalls plagued many areas of Ontario and Quebec, especially near open lakes, causing them to be snowier than March and April.

The lingering spring-time chill, along with May snows, fit the mood of the nation, frozen in place. In some ways, Mother Nature made it easier for Canadians to self-isolate indoors to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Mother Nature joined with public health officials to keep people dutifully two metres apart in the warmth of their own homes. Further, on May weekends, because people who normally went away to cottages or cabins tended to stay put, there was a slower start to the wildfire season compared to most.

7. The year’s most powerful tornado

In a year with at least 77 tornadoes across Canada, the highest-rated and therefore the most powerful tornado occurred on August 7 in southwestern Manitoba near the rural municipalities of Pipestone and Sifton. On August 6, individual storm cells produced large hail, powerful winds and torrential downpours in Alberta. The next day, the low-pressure system shifted eastward posing a threat with large hail, heavy rains, and damaging winds through the afternoon and early evening hours in eastern Saskatchewan and western Manitoba. Environment and Climate Change Canada issued a tornado warning at 7:49 pm and five minutes later a monster funnel cloud filled the sky and grounded as an EF-3 tornado near Scarth, 13 km south of Virden, Manitoba. Violent winds blew over 200 km/h lasting between 10 and 15 minutes, leaving a 9-km long damage trail of farm buildings, chewed up grain silos, crushed steel fertilizer bins, snapped trees, felled powerlines and wooden utility poles, with scattered debris across yards and fields.

A man from the Sioux Valley Dakota Nation witnessed the twister’s ferocious strength when winds uprooted a pine tree and tossed it onto his Jeep’s roof seriously injuring him. Within seconds, winds blew out the vehicle’s windows and started rolling it for 150 m before it settled in a ditch. At the scene, he witnessed the tragic sight of the tornado lifting a pickup truck and tossing it a kilometre away. Police and other first responders found the crushed truck. Tragically, its two teenage occupants from nearby Melita, Manitoba had been ejected and did not survive. The Scarth tornado was the strongest twister recorded in Canada in 2020, reaching wind speeds estimated as high as 260 km/h.

6. Record hurricane season and Canada wasn’t spared

Meteorologists predicted another “active” Atlantic hurricane season in 2020, but a record season was more like it! The tally at the official end of the season was 30 named storms, 13 hurricanes of which 6 became major hurricanes– approaching three years’ worth of storms in one. Named storms went from Arthur to Wilfred and started again from Alpha to Iota. The “hyper” storm season reflected a warm multi-decadal cycle of high storm activity that began in 1995 and broke the record for the number of named storms in a single season set back in 2005. As forecasters are getting better at detecting even weaker storms, it was no surprise that once again a couple of them showed earlier on the map. For the record sixth year in a row, a named storm formed in the Atlantic basin prior to the official start of the season. Fay was the earliest sixth named storm, forming almost two weeks earlier than Franklin did in 2005. And Eta was an October storm whereas the 2005 Eta storm lasted until January 2006.

The hurricane season began quickly and stayed active right to the end. While a record number of tropical storms swirled their way through the North Atlantic, eight named storms entered the Canadian Hurricane Centre (CHC) Response Zone. None of those storms had nearly the impact of those in the United States, the Caribbean and Central America. By July 10, the remains of an exhausted tropical storm Cristobal combined forces with a system that swept out of the Rockies to bring several hours of wet and breezy weather across Ontario and Québec and into Labrador before dying out near Greenland. Hydro-Québec reported as many as 130,000 power outages in the Laurentian, Montreal and Montérégie areas. The remnants of tropical storm Fay came ashore in New Jersey on July 10 before heading north and east dumping between 50 and 100 mm of rain in Québec. The day before, Fay’s moisture fed some hot and humid air sitting over Ontario along with a passing cold front dumping welcomed rain on a dry province. Pockets of extremely heavy rainfall (up to 150 mm) occurred from Kingston to Québec City. Post-tropical storm Isaias made its way through Québec’s Eastern Township on August 5 packing strong winds between 75 km/h in Montreal to 90 km/h at lle d’Orléans and heavy rainfall between 50 and 90 mm in just a few hours and 125 mm in the Charlevoix region. Apart from some breezy hours, a transitioned Isaias left 60,000 Eastern Québecers without power on August 5. Remnant moisture from a weakened Hurricane Laura contributed to a rainfall event along the lower St. Lawrence, the Saguenay, Lac-Saint-Jean, Gaspé and the North Shore in Québec and in the Maritimes at the end of August before tracking across Newfoundland to Labrador. Rainfall amounts between 40 to 70 mm that fell provided welcome water for suffering crops and helped replenish some of the near-empty wells, streams and ponds. Moisture from the remnants of Hurricane Sally fed into a low-pressure system bringing over 100 mm of rain to Eastern Newfoundland, although the peak occurred at Placentia on September 18 and 19 with a whopping storm rainfall total of 206 mm. In mid-October, the remnants of Hurricane Delta added a lot of moisture in Québec to a system coming from the West. Heavy rains above 60 mm fell from Estrie to the Gaspésie.

Teddy was no Dorian or Juan

The season’s most impactful tropical storm in Canada, Teddy held few surprises for forecasters as it began its trek south of Bermuda on September 23 making a beeline for Nova Scotia at the beginning of the fall season. Teddy was the earliest 19th named Atlantic storm on record and was a major Category 4 strength south and east of Bermuda before weakening to a ragged but larger post-tropical storm about 12 hours before making landfall about 100 km east of Halifax on September 23. Although Teddy had transformed into a post-tropical storm, its sustained winds stayed at hurricane-force prior to making landfall. Parts of southeastern New Brunswick, eastern P.E.I. and western Nova Scotia received copious amounts of rain. Officials and residents in the Maritimes were well prepared, which lessened the storm’s impacts. Unlike Dorian a year before, Teddy’s winds were less forceful and the storm moved through more quickly. While no Dorian, Teddy was the most impactful Canadian tropical storm in 2020. That being said, the storm churned up 15-metre waves offshore, dropped over 100 mm of rain in places and produced maximum wind gusts over 130 km/h. Cape Breton Island took the biggest hit with 132 mm of rain and wind speeds of 145 km/h. Halifax received around 100 mm of rain and 80 km/h winds. A maximum significant wave of 12.8 m occurred at an off-shore buoy. Leafed trees created an added risk to downed limbs and power outages. Parks Canada closed some national parks in advance of the storm’s arrival and as a precaution some schools were closed, restrictions were put on the Confederation Bridge, and ferry and flight services were curtailed.

5. St. John’s “snowmageddon”

Meteorologists called it a bomb cyclone, where a storm’s atmosphere dropped 24 hPa (degrees of pressure) in 24 hours. For townies in St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador it was “Snowmageddon” – the fiercest blizzard of a lifetime in a city known for its punishing winter storms. On the morning of January 16, a deep low-pressure system situated in western New York tracked through the northeastern United States before continuing onwards to Newfoundland’s Avalon Peninsula – a normal track for a mid-winter storm. For much of the next day, the storm deepened and strengthened to “bomb” status, its pressure dropping more than 54 hPa in 48 hours. Snow began falling early on January 17, intensified during the day, before easing up later overnight. Blizzard conditions prevailed for 18 straight hours with visibilities of 200 metres or less. St. John’s International Airport broke its historic daily snowfall record with 76.2 cm and had to stay closed for six days. Nearby, Mount Pearl and Paradise reported 90 cm of snow over 28 hours. Snowfall intensity of 10 cm an hour was impressive. The last time St. John’s saw something close to 75 cm of snow was in April 1999, when the pre-storm ground was snow bare. The January storm started with 40 cm of snow already sitting on the ground. In fact, for 27 days starting on Christmas Eve there was only one day without snowfall, New Year’s Eve, for a total of 220.8 cm in that period. Winds on January 17 were also impressive, reaching hurricane force at 160 km/h along the coast. The deep low and strong winds also generated a significant storm surge with a wave height of 8.7 m on January 18, damaging docks, wharfs and yachts. But it was all about the snow! Most times you couldn’t tell if it was snowing or just blowing around. Monster drifts were higher than doorways, which meant people often had to dig from the inside out. The super-sized storm left piles of snow higher than houses. The city was entombed in snowdrifts. There was even an avalanche in the middle of downtown. St. John’s, claiming to be the snowiest major city in Canada, earned its reputation and declared a state of emergency along with 11 other nearby communities. This marked the city’s first in 36 years – which lasted more than nine days. Another 10 to 20 cm of snow fell over the next days making cleanup efforts even more challenging. That is when 625 Canadian Armed Forces personnel arrived for a week or more to help dig out the city by clearing roads, attending to the elderly and sick and ensuring residents got medical care.

Plugged narrow streets became an enormous struggle for crews cleaning more than 14,000 km of city roads. Power outages occurred to more than 20,000 hydro customers. All businesses were ordered closed and all vehicles except emergency ones were prohibited from operating. Even government snowplows were taken off the streets. Mail delivery was halted but even when resumed, mailboxes were buried; blood donor clinics closed; even funerals had to be postponed. Homeowners ran out of supplies and lined up at grocery stores five days after the storm ended when they were able to reopen. Insurer costs exceeded $17 million, covering only a fraction of snow removal costs and economic losses. The monster snowstorm on January 17 was the big talk for weeks in the city, but it also made news worldwide from the United Kingdom to Turkey to Australia. With 12 days to go in January, St. John’s broke the record for their snowiest January since records began, totalling 166 cm from January 1-19, 2020. No wonder the local townies called it January.

4. Endless hot summer in the East

Following a cold spring with frost and snow in the first half of May, the weather in Central and Eastern Canada soon turned from slush to sweat. The long weekend in May – often the unofficial kick-off of summer – proved prophetic and a trendsetter. In Eastern Canada, it was the summer of summers – coming early and staying warm until almost Labour Day. Overall, it was either the fourth or fifth warmest summer in 73 years and the warmest since 2012. Temperatures started exceeding 30°C on May 25 and humidex values soared close to 40 in Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick.

On May 27, Montreal hit 36.6°C, its hottest May temperature ever. In fact, it was the second-highest reading ever in Montréal! The only hotter day in 15 decades was 37.7°C on August 1, 1975. In Quebec, 140 temperature records were eclipsed in June, and July saw even more records broken. Incredibly, Sept-Iles touched 36.6°C on June 18th – an all-time record for the area. Before the second week of July, Ottawa had already as many days above 30°C, with four exceeding 35°C, as it would normally see an entire summer. Normally such sizzle occurs once every 10 years, not four times in one summer. July 2020 wasn’t the hottest July on record at the Ottawa International Airport, but you’d have to have been alive in 1921 to have experienced a more sweltering one in the city with records dating back almost to Confederation. In eastern and southern Ontario and southwestern Quebec, temperatures remained above normal almost continuously for 60 days from mid-June to mid-August. In Montréal and Ottawa, the average temperature for the hot spell was the highest in 145 years. At Toronto, July featured 15 occasions when nighttime-temperatures stayed above 20°C. Lasting heat also baked parts of the Maritimes. New Brunswick’s capital Fredericton had 20 days above 30°C, not the normal nine, and the most in 50 years. In addition, the city recorded 14 days with a maximum between 29° and 30°C. Summerside, Prince Edward Island had ten 30°+days compared to the average of one. The summer warmth at times headed westward to Manitoba. Winnipeg exceeded its hot 30° days by almost twice the usual number. Everywhere in the east, soaring temperatures and thick humid air caused breathing difficulties. As temperatures sizzled, it also meant deteriorating air quality on many days, adding to the high air quality health risk. The summer raised concerns inside long-term care facilities for residents with underlying health conditions facing COVID-19 outbreaks. For other Canadians, usual hot weather shelters such as air-conditioned malls, libraries, recreation centres, movie theatres and public swimming pools were often closed due to COVID-19, adding to the breathing and heat respite challenge.

With the kind of summer Ontario had, it was not a surprise that the Great Lakes were as hot as a hot tub. Surface water temperatures ranged between three and five degrees higher than normal except for larger and deeper Lake Superior. According to satellite reconnaissance on July 10, Lake Ontario’s average surface temperature reached around 25°C – a record this early in summer and on par with the highest temperatures in any month since satellite data collection began.

3. Fort McMurray’s flood of a century

For the second time in four years, residents of Fort McMurray, Alberta were forced out of their homes. This time it was water, not fire. Severe ice jamming on a 25-km stretch of the Athabasca River caused water to back up on the adjacent Clearwater River, flooding much of downtown at the end of April. It was said to be the most significant flooding in more than a century. In a matter of hours on April 26, ice clogging raised water levels on Fort McMurray area rivers between 4.5 and 6 metres. The sheer size of the ice prevented the use of common ice-jam breaking options, such as explosives. Instead, what nature started, nature had to stop. An unprecedented two months of extreme cold as much as 10 degrees below normal, followed by a week of rapid warmth, lots of sunshine and warm rains prompted continued melting of the ice exacerbating the flood but continuing to mitigate it too. For more than a week, 13,000 residents in the lower townsite of Fort McMurray had to evacuate. Another ice jam on the nearby Peace River forced 450 people from their homes in Fort Vermilion, Alberta. Many customers went without power or gas service for nine days. States of local emergency and boil water advisories were in effect in both Fort McMurray and the surrounding municipality adding to the state of emergency declared a month earlier due to COVID-19. Some residents were forced out of their homes after weeks of isolation due to the pandemic. Emergency measures officials did a remarkable job managing evacuations in one of the world’s first natural disasters during a public health crisis. In spite of the efforts of thousands of volunteers and workers engaged in bailing and sandbagging to protect infrastructure including the hospital, essential businesses were unreachable in the submerged downtown core, and only a handful of grocery stores remained open, causing a strain on supply. Tragically, a man from the Fort McKay First Nation, about 60 kilometres north of Fort McMurray, drowned after he and another were caught by rising waters of the Athabasca River. Most water damage was to commercial property downtown where 1,230 structures were damaged from both overland flooding and sewer backup. Hundreds of abandoned cars and trucks were completely submerged. Huge ice chunks and piles of silt lay on the golf club and two small bridges on the course were smashed. The Insurance Bureau of Canada estimated the cost of the flooding from nearly 3,000 claims totalled above $562 million with 90% paid out to commercial properties.

2. BC’s September skies: all smoke, no fires

Statistics from the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre reported a second consecutive quiet fire season across British Columbia in 2020 following two of the busiest years ever in 2017 and 2018. The number of fires province-wide this year was down to 629 or a third of the fires in the record year of 2018. Most shocking, burned hectares of woodlands were only 1% of that consumed two years earlier and 4% of the average areal burn over the past decade. Whereas there were only a few home-grown fires, owing to a cooler and wetter spring, there was a record amount of imported wildfire smoke in September. Visible from space, dense smoke plumes from forest fires in the U.S states of Washington, Oregon and California travelled northward into British Columbia’s southern airshed. Residents from Victoria and Vancouver east to Kamloops, Kelowna, and in the Kootenay region faced some of the worst air quality in recorded history and some of the poorest and unhealthiest air in the world. For eight consecutive days in mid-September, about four million British Columbia residents, urban and rural, and young and old smelled smoke and breathed foul air. Special Air Quality Statements were issued by Environment and Climate Change Canada, as air-cleansing rains and pollution-dispersing marine winds were absent in the first half of September. Beautiful British Columbia didn’t look so beautiful! Residents with underlying respiratory and cardiovascular conditions were especially vulnerable, as the fine particulate matter was six times levels registered from the home-grown fires of 2017 and 2018. The long-term health effects for all residents are unknown. Vancouver and Victoria were especially dark and smoky. Vancouver recorded 171 hours of smoke and haze in September with one bout that lasted 120 consecutive hours over four full days from September 12 to 15. Victoria was no less impacted with 195 hours of smoke/haze, including 186 consecutive smoke-filled hours around the 15th of the month. Both cities registered 70% to 80% more smoky hours above their previous record numbers from August 2018.

Around the Labour Day weekend, a high-pressure system building over northern British Columbia produced strong gusty winds over the southern half of the province. The same weather system ushered in a couple of days with record high temperatures warmer-than-normal and pulled in smoke from massive fires burning across the border from the United States. A dense, fog-like shroud turned daylight into smoke-tainted twilight, blue skies to leaden grey with an acrid-burning smell and sunrises an eerie blood red. Smoky skies bulletins for the southwest prevailed for 11 days, compounding a public health crisis already posed by the COVID-19 virus. At times, the thick layer of smoke aloft prevented sunshine from getting in and heating up the ground thus chilling temperatures by 6 to 10 degrees across the West. Around September 18, a fall frontal system from the Gulf of Alaska brought rains and winds to the Coast to start flushing out the smoke and improving breathing. Wildfire smoke wafted across the border into Alberta. Calgary was spared but smoky skies prevailed in southwest Alberta, near the Rockies. Further east, satellite imagery on September 14 and 15 showed plumes of smoke drifting across the country extending as far as Europe. American wildfire smoke moved back into southwest British Columbia on September 30 for a very short time, but the air quality was nowhere as bad as it was earlier in September.

1. Calgary’s billion-dollar hailer

Calgary, Alberta endured more than its share of stormy summer weather in 2020. The season featured frequent hailfalls with grapefruit-size stones, powerful wind speeds, tornado scares, dark funnel clouds, lightning-filled skies, torrential rains, and flash flooding. The city lived up to its reputation as the hailstorm capital of Canada. The Insurance Bureau of Canada sees hail as such a threat in the city that it sponsors a cloud-seeding program in order to diminish the size of urban hailstones – a pea-size stone does much less damage than ones the size of tennis balls. The June 13 hailstorm was Canada’s costliest and the fourth most expensive insured natural disaster in history with Canadian insurers estimating the dollar value of the 63,000 claims (minus crop losses) at about $1.3 billion. More than 32,000 vehicles were extensively damaged with cracked and smashed windshields with vehicle write-offs totalling $386 million.

As was frequently the case this summer, on June 13 warm, humid air was positioned over Alberta generating multiple rounds of severe thunderstorm cells. With colliding winds at various heights over southern Alberta, the resulting wind shearing kept the large, long-lived thunderstorms going. Around 7 p.m. MDT, a hail core scraped over northeastern Calgary, visibility dropped to half a kilometre, and temperatures fell 5 degrees in less than six minutes. Hail the size of tennis balls and golf-balls ricocheted out of the sky propelled by wind speeds up to 70 km/h. Pounding hail shook houses, broke windows and downed trees. Crashing hail dimpled vehicles and riddled house siding with millions of dents. The violent hailstorm smashed skylights, flattened flowerbeds and turned backyard vegetable gardens into coleslaw. Streets and intersections were flooded, and manhole covers were lifted. In its wake, slushy hail drifts 10 cm deep piled up along highways, and were still evident the next day. Power outages knocked out service to more than 10,000 customers. Train and bus services were suspended due to flooding. Outside the city, the massive hailstorm decimated hundreds of thousands of hectares of young wheat, canola and barley.

Regional weather highlights and runner-up events in 2020

National

- Another “not-cold” year in Canada – 24 in a row

- Quiet Canadian wildfire season

- Arctic Ocean – more water than ice

- Canadian ice shelves melting away

Atlantic Canada

- Rough landing in snowy Halifax

- Winter’s first big storm slams Eastern Newfoundland

- Record January snowfall in Sydney

- Newfoundland’s stormy February

- Powerful storm brings down a dome in Cape Breton

- Blustery winds punish Maritimes at end of February

- Easter Friday weather bomb

- Flooding again on the Saint John River?

- Foul weather on Mother’s Day

- Microburst and century flooding strikes Fredericton

- Spring-summer dryness in the Maritimes

- Big snow in “Big Land”

Québec

- Winter’s first storm with all kinds of precipitation

- Snow to celebrate

- February snows gridlock Québecers

- Late February storm and surge at Québec City and eastward

- Late winter flood threat

- Easter weekend features snow, surges and coastal flooding

- Wildfires out of control in the Saguenay

- Microbursts and Québec’s first tornado

- Flooding rains and hail inflict major losses

- More tornadoes and flooding in July

- Pre-Thanksgiving hail and wind costs millions

Ontario

- January’s weekend storms – three in a row

- Rideau Skateway’s 50th season – never fully opens

- Texas storm turns on lake-effect snow engine

- Heavy rains and wind-driven flooding around Victoria Day

- Summer’s first heat wave fuels severe thunderstorms

- More tornadoes in Ontario. Perhaps?

- Flash flooding in Toronto’s west end closes beaches

- Ontario wildfires confined to Red Lake region

- Dry land farming

- Record number of waterspouts on the Great Lakes

- Three-day rain event across Ontario

- Another year of high Great Lakes water levels

- Summer’s last hurrah with storm in October

- Witches of November storm

Prairie Provinces

- Brutal cold, even for the Prairies

- Widespread June wind-hail-rain in Saskatchewan

- West Manitoba June Deluges

- Tornado day in Saskatchewan

- Northern Saskatchewan too wet for grain and rice producers

- Thought to be tornadic, straight-line winds strike Manitoba

- Edmonton rainstorm floods hockey venue

- Calgary’s other hailstorm

- Finally, summer heat in the Western Prairies

- Big trough country

- “Great” harvest with some exceptions

- Pre-winter weather chills the second half of October

- Weather dome over the west

British Columbia

- BC’s atmospheric river

- Toughest part of winter in mid-January

- Soggy storm raises water flows and levels

- Vancouver’s big wet and long dry

- May heat not a trend

- Rare Vancouver Island tornado

- Finally, heat returns to the southwest

- Wettest Canadian city becomes soggier

- Quiet wildfire season

- Freshet flooding from spring through fall

- Early winter outbreak

- BC’s “king tide” storm

North

David Philips, Les dix événements météorologiques les plus marquants, Météo Canada