La diminution du nombre de stations et l’automatisation des observations de l’épaisseur de la neige en surface posent des défis importants pour les applications nécessitant des données cohérentes à long terme sur l’épaisseur de la neige en surface au Canada.

– Par Ross Brown –

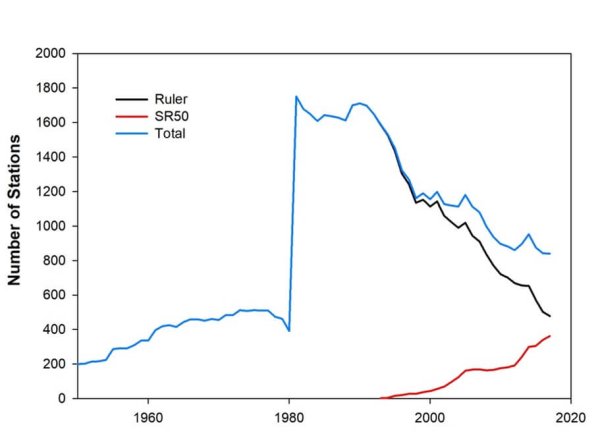

Les stations d’observation de l’épaisseur de la neige d’Environnement et Changement climatique Canada (ECCC) représentent le principal réseau d’observation de l’épaisseur de la neige en surface au Canada, fournissant des données météorologiques et climatologiques cruciales. En revanche, l’acquisition cohérente à long terme des variations de l’épaisseur de la neige est mise au défi par deux phénomènes : premièrement, une diminution rapide d’environ 50 % du nombre de sites mesurant quotidiennement l’épaisseur de la neige depuis 1995; deuxièmement, un passage continu des observations manuelles à des observations automatisées de l’épaisseur de la neige qui représente un changement fondamental dans la façon dont les observations de l’épaisseur de la neige sont effectuées.

Les mesures manuelles quotidiennes de la neige avec une règle représentaient la méthode standard pour mesurer l’épaisseur de la neige par ECCC de 1941 à 1994. Le Campbell Scientific Sonic Ranger SR50 a été officiellement mis en service pour ECCC en 1993. La principale différence entre les observations manuelles et celles du SR50 est que ces dernières sont effectuées en un seul point fixe, tandis que les premières incluent une tentative de moyenne spatiale par l’observateur. Les deux méthodes devraient produire des résultats similaires lorsque la couverture neigeuse est relativement homogène, mais c’est rarement le cas dans les environnements venteux, comme l’Arctique et les Prairies, où le manteau neigeux est peu profond et sujet à de fréquentes dérives et affouillements.

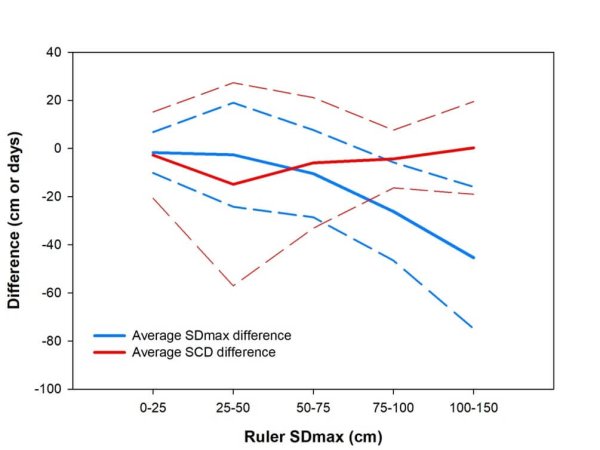

Au début des années 2000, ECCC a tenté de résoudre le problème de l’échantillonnage en mettant en place trois capteurs SR50 étroitement répartis, ce qui est la norme actuelle dans toutes les auto-stations d’ECCC. Par contre, le processus de combinaison opérationnelle des informations provenant des trois capteurs n’a pas encore été défini, et seules les données d’un capteur choisi arbitrairement sont actuellement signalées. Une comparaison entre des observations manuelles à la règle et des auto-stations voisines équipées de capteurs SR50 par Brown et coll. (2021) a montré que les capteurs soniques ont observé un nombre similaire de jours avec de la neige au sol, mais ont systématiquement sous-estimé les épaisseurs de neige rapportées manuellement, l’ampleur de la sous-estimation augmentant avec la profondeur. La différence systématique entre les deux méthodes de mesure a été prise en compte par Brown et coll. (2021) dans une évaluation actualisée des tendances de la couverture neigeuse de surface au Canada. Les ensembles de données élaborés pour cette analyse, y compris les séries de stations d’épaisseur de neige quotidiennes historiques à qualité contrôlée, sont accessibles via le lien fourni dans la citation.

Après avoir passé plusieurs décennies à travailler avec les données d’épaisseur de neige d’ECCC et à se tourmenter à leur sujet, voici plusieurs recommandations qui aideraient grandement ECCC à mieux répondre aux besoins des utilisateurs qui ont besoin de données d’épaisseur de neige cohérentes, à long terme et fiables. Premièrement, un effort urgent s’impose pour améliorer la qualité des données du capteur sonique archivées par ECCC. Deuxièmement, des efforts supplémentaires sont nécessaires pour effectuer un contrôle de qualité des observations incluses dans les archives climatiques d’ECCC. Troisièmement, les données sur les sites devraient être facilement accessibles, y compris les photos montrant l’emplacement des capteurs dans diverses conditions de couverture neigeuse. Enfin, il est nécessaire de déterminer (et de protéger) les stations ayant des mesures manuelles de l’épaisseur de neige cohérentes et à long terme. Ces stations, dont le nombre est actuellement inférieur à 100, constituent la référence pour documenter la réponse de l’épaisseur de la neige au changement climatique, et leur importance pour ce besoin et d’autres ne peut être surestimée.

Declining numbers of stations and automation of surface snow depth observations pose important challenges for applications requiring long term consistent surface snow depth information over Canada

– By Ross D. Brown –

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s (ECCC) snow depth observing stations represent the primary surface snow depth observing network in Canada, providing real-time input on surface snow cover conditions that contributes to increased skill and reduced air temperature biases in forecast models. The archived data also have important downstream applications such as estimation of design ground snow loads analysis of snow cover impacts on ground heat transfer and permafrost, and assessment of variability and change in Canadian snow cover. These applications require long-term, consistent information on snow depth variations over time. However, this requirement is challenged by two phenomena: first, a rapid decline of approximately 50% in the number of sites measuring daily snow depth since 1995; second, an ongoing shift from manual to automated snow depth observations that represents a fundamental change in the way snow depth observations are made. Currently, about 50% of the total observing network uses an ultrasonic ranging sensor (‘SR50’), including more than 80% of the network above 55°N. Figure 1 shows the historical evolution of the number of stations in the network by measurement method.

To provide some context for Figure 1, regular daily ruler measurements of snow depth began in 1941 at principal observing stations with spatial coverage mainly confined to southern Canada until the mid-1950s when the synoptic station network expanded into the Arctic. Prior to 1941, snow depth observations were typically only made at the end of the month and at a relatively small number of sites. For the weather trivia buffs, the earliest recorded snow depth observation in the ECCC historical archives was made at Chaplin, Saskatchewan, in 1883. The manual observing network underwent a major expansion after 1980 when daily snow depth observations were initiated at volunteer climate stations, with a peak of over 1600 active stations during the 1981-1994 period. The protocol for manual ruler observations has remained essentially unchanged since 1941, with observers instructed to record the average of a series of measurements avoiding snowdrifts. Allowing the manual observer to select the number and location of measurement points introduces some subjectivity, but the averaging of these measurements helps capture the ‘typical’ local conditions.

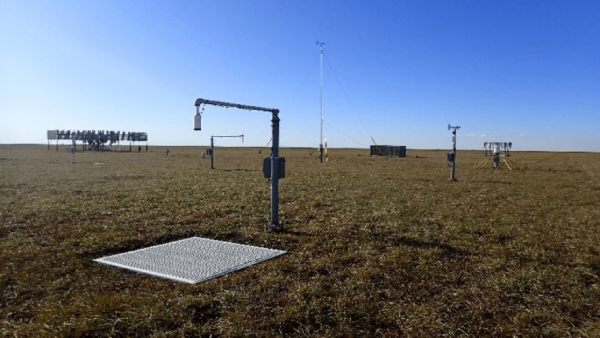

The mid-1990s saw the start of a major effort to automate the ECCC surface observing network in response to declining budgets and network modernization: automation offers the potential for increasing network coverage in data-sparse areas and for providing potential all-weather quantitative data for time intervals of one hour or less to meet World Meteorological Organization requirements. The snow depth measurement sensor used in ECCC automated weather stations is based on a prototype developed by Dr. Barry Goodison of the Hydrometeorology Division of the Canadian Climate Centre in the early 1980s. The inspiration for the sensor came from a commercially available ultrasonic ranging kit from Polaroid Corporation that used the travel time of an acoustic signal from a reflecting surface to estimate the distance to the surface. The sensor went through several iterations during the late 1980s and early 1990s and officially went into service for ECCC in 1993 as the Campbell Scientific Sonic Ranger SR50, updated in 2007 to the more compact SR50A. Figure 2 shows a typical SR50 sonic sensor configuration above a fixed artificial target. The artificial target prevents the growth of vegetation under the sensor and provides a stable flat surface for reflecting the sonic pulse when there is little or no snow under the sensor. Various evaluations have demonstrated the sensor measures snow depth (directly under the sensor) with an error of less than 2 cm. However, the sensor can be unreliable during heavy snowfall or blowing snow events when the acoustic signal is obscured.

The key difference between manual and SR50 observations is that the latter is made at a single fixed point, while the former includes some attempt at spatial averaging by the observer. The two methods should give similar results where the snow cover is relatively homogenous, but this is rarely the case in windy environments, such as the Arctic and Prairies where the snowpack is shallow and subject to frequent drifting and scouring. In these environments, acoustic sensors are faced with a sampling problem (how can a single point observation be considered “representative”?), plus issues with unreliable readings during blowing snow conditions. In the early 2000s ECCC attempted to address the sampling issue with the implementation of three closely-distributed SR50 sensors, which is the current standard at all ECCC autostations. However, the process of how to operationally combine the information from the three sensors has not yet been defined, and only data from one arbitrarily chosen sensor is currently reported. A comparison of manual ruler observations with nearby autostations equipped with SR50 sensors by Brown et al. (2021) showed that sonic sensors observed similar numbers of days with snow on the ground, but systematically underestimated manually reported snow depths, with the amount of the underestimation increasing with depth (Fig. 3). The systematic difference between the two measurement methods was taken into account by Brown et al. (2021) in an updated assessment of surface snow cover trends in Canada. The datasets developed for this analysis including quality controlled historical daily snow depth station series can be accessed via the link here.

Having spent several decades working with and agonizing over ECCCs snow depth data, here are several recommendations that would greatly help ECCC better meet the needs of users who need consistent, long-term, reliable snow depth data. First, an urgent effort is needed to improve the quality of the sonic sensor data archived by ECCC. Fully utilizing the triple sensor configuration is an important first step (i.e. archiving and making available the hourly observations from all three sensors), along with ensuring that the siting of the three sensors is optimized to provide representative estimates of the snow depth in the vicinity of the observing site. This is especially important in exposed, windy environments with strong spatial variability in snow distribution. Second, more effort is needed to carry out quality control of the observations included in the ECCC climate archive; this includes additional data consistency checks (the observations from the three sensors would greatly facilitate this process) and the archiving of key metadata, such as measurement method history, along with the data so that users are aware of the nature of the measurements they are working with. Third, site information should be readily available including photos showing the location of the sensors under a variety of snow cover conditions. Finally, there is a need to identify (and protect) stations with long-term, consistent manual snow depth measurements. These stations, of which there are currently less than 100, represent the reference for documenting the snow depth response to climate change, and their importance for this and other needs cannot be overstated.

Note: the link to the snow data provided in the published paper Brown et al. (2021) has been replaced by the link provided here. Apologies for any inconvenience this may have caused. A big thank you to Colleen Mortimer of the Climate Processes Section of ECCC for organizing this.

Ross Brown worked on snow-related research at Environment and Climate Change Canada for more than 25 years, and published as lead and co-author more than 60 peer-reviewed articles. A particular interest was using multiple sources of snow cover information to obtain new insights into snow cover variability and change, and the associated uncertainty. Ross was a contributing author to the IPCC 2nd to 5th assessment reports from 1995 to 2013. Ross retired from ECCC in March 2018.

d’observation de l’épaisseur de la neige, Environnement et Changement climatique Canada, Ross Brown