Extraits du journal de la station météorologique d’Eureka, 1947 à 1948

– Par John Gilbert –

La station météorologique d’Eureka, située dans le Grand Nord canadien, a récemment célébré son 70e anniversaire. Cette station météorologique éloignée revêt une importance mondiale, puisqu’elle soutient la météorologie opérationnelle et la recherche atmosphérique sur des sujets essentiels à la compréhension du temps et du climat, y compris la surveillance météorologique synoptique et aérologique horaire et la détection des changements atmosphériques.

La lecture des journaux de la station nous en apprend beaucoup sur la vie à Eureka durant ces premières années. Les entrées consignées s’étendent du premier jour de la station, en avril 1947, jusqu’à très récemment. Les habitants et les visiteurs d’hier et d’aujourd’hui ont enduré des événements météorologiques extrêmes, des accidents et des catastrophes dans le cadre de leur service dévoué à l’avancement de la compréhension scientifique de l’environnement arctique. L’échantillon d’entrées partagées ici est tiré des journaux de la station rédigés en 1947 et 1948. Il nous donne un aperçu des (més)aventures de la première année de la station d’Eureka.

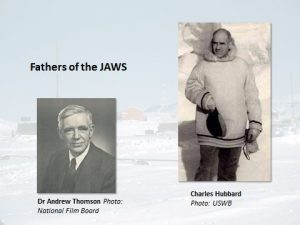

The Eureka Weather Station, situated in Canada’s far North, recently celebrated its 70th birthday. Supporting operational meteorology and atmospheric research on topics that are essential for the understanding of weather and climate, including hourly synoptic and aerological weather monitoring and the detection of atmospheric change, this remote weather station is of global significance. The Station came in to being in February of 1947, when an agreement between Canada and the United States to establish five Joint Arctic Weather Stations (JAWS) staffed by Canadian and American personnel was reached. Under JAWS, Eureka and Resolute were the first weather stations established in 1947, followed by Isachsen and Mould Bay in 1948 and Alert in 1950. The Joint project was led by Dr. Andrew Thomson, head of MSC and Charles Hubbard, US Weather Bureau.

That same year, in April, the first station, Eureka on Ellesmere Island (near 80 degrees N., 86 degrees W.) was established by airlift from Thule, Greenland. It was then the farthest north station and post office in the world. Perhaps reflecting the international character of the Eureka station, the Officer-in-Charge (OIC), Jud Courtney, was a Newfoundlander and the US Executive Officer, Per Stoen, was a Norwegian-born American.

A lot can be learned about life at Eureka in those early years from the station journals, in which entries were made from the first day of its establishment in April 1947 until very recently. Past and present inhabitants and visitors have endured extreme weather events, accidents and disasters as part of their dedicated service to the advancement of the scientific understanding of the Arctic environment. A sampling of entries shared here, from the station journals of 1947 & 1948, gives us a glimpse into just some of the (mis)adventures of Eureka’s first year.

An Accident with Caustic Soda

December 3 [1947] Wednesday: [Journal entry by Murray Dean, Met Tech]. First serious accident on the station today. While making hydrogen, Courtney received a shower of caustic soda flakes in the face, and some went into the right eye. The eye was flooded with water and treated with boric acid ointment, but during the time before he could reach the operations building for this treatment, the eyeball was severely blistered and vision impaired. Will possibly be blind in this eye for some time.

December 4 [Journal entry by Courtney]: Cannot see well enough myself to take ascents or do any work that requires use of eyes. I find the left eye has been affected too; some of the soda dust must have gotten in there. Treatment with boric acid continuing…..I can operate a typewriter by touch, and write the reports mainly from memory and from the station journal notes which are read to me. I hope the eyes have suffered no permanent injury; they seem to be OK and I can see very dimly in bright light.

December 6: The right eye does not seem to be any better, although the left one is clearing up now. This is causing some worry here on the station and we are afraid some permanent damage may have been done. However, only time will tell in the absence of competent medical diagnosis.

December 12: Eye is improving slowly, but [I] cannot tell yet if any permanent damage has been done.

December 17: The eye appears to be going to heal of its own accord, but is still badly inflamed and brings on headaches when used. [In 2012 Jud, then in his 90s, viewed and commented on Eureka photos – without the need for glasses].

December 28: Now, just when my eye was coming along fine, developed an infection of the eyelid. The eyeball is still inflamed but sight is almost normal in this eye now and we have stopped worrying about it.

The Lost Aircraft

December 19: Temperature minimum last night -51º F and still getting colder.

December 20: Personnel are being given a few days off in order to get Xmas mail written and make photographic Xmas cards, since the non-arrival of the plane in October did not give them a chance to get them any other way.

December 23: Aircraft arrived here tonight unexpectedly. No flight plan from Thule and aircraft did not call this station until ten minutes out from here…..homemade flare pots [toilet paper in coffee cans soaked in fuel oil] were used for the strip this time. Change of one man on staff on this aircraft. [Robert] Tyrer was relieved by Walker of DOT. ….The moonlight was weak and deceptive….With the moon up we shall have to take advantage of the light to get in a supply of ice sufficient to last until next moon. [Robert Tyrer left on the plane which flew to Resolute where J.D. Cleghorn, OIC Resolute, joined the flight enroute to Goose Bay

December 24, Wednesday: Christmas Eve, and we had planned to celebrate the season as best we can under the odd shift hours we work. BASOPS reported today that the aircraft with [Robert] Tyrer aboard has gone down between Resolute Bay and Goose Bay, and has not been located. Nobody feels much like celebrating anything now. However, they are in good country to go down if they were on course, and there is every hope they have made a safe forced landing.

December 25, Thursday: Still waiting for news of the aircraft. The Xmas dinner went well, but without much heart. The tree was not even set up.

December 26. Friday: Good news today. The aircraft has been located and all personnel are safe and well. Aircraft made a forced landing close to Goose Bay, probably on one of the many lakes in that region [Dyke Lake, Labrador]. Personnel will be flown out to Goose Bay tomorrow. [The plane was abandoned and sunk to the bottom of Dyke Lake for 51 years].

December 27: According to commercial news, the crew and passengers of the aircraft are safe in Goose Bay tonight.

A sequel: The story of the 1998 recovery of the wrecked plane is told in Nicholas A. Veronico’s book: Hidden Warbirds II: More Epic Stories of Finding, Recovering, and Rebuilding WWII’s Lost Aircraft (2014).

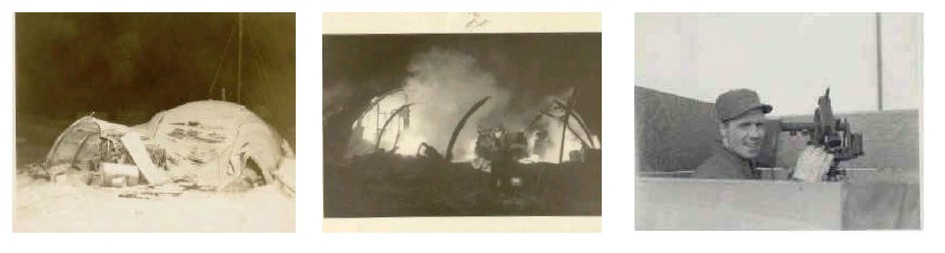

A Disastrous Fire

Fire and appendicitis were the two big fears at these remote weather stations.

December 16 [1948]: (Murray Dean, OIC writing.): We have not been heating the RAWIN (Radar Wind Sounding) shelter due to danger of fire for several weeks now.

December 24 [1948]: Lowest temperature of the season, minus 51.8º F.

December 25 [1948]: This was the date of the worst disaster that could befall us. Fire wiped out our complete power supply, much other equipment and stocks, and much hard work. …..That until today everything was running so smoothly and was so pleasant should have been a warning to us that our good luck could not continue. This was also Christmas. We could not rejoice.

December 26 [1948]: Communications with Resolute continue unbroken. The small SCR 694 performs admirably with its hand-cranked generator. We learn from Resolute tonight that only because of a fortunate incident were they saved from experiencing our plight this evening. They were fortunate in discovering a fire in their power-shed and were able to stop it before any damage was done. This is small consolation to us, however.

The Canada/US Agreement was initially limited to five years. A “Five Year Report” was written in 1952 and the arrangement was extended to span a total of 25 years, after which Eureka became a solely Canadian weather station when the stations were re-named “High Arctic Weather Stations”.

The legacy of the pioneering meteorological and atmospheric research at Eureka, started over 70 years ago, continues through the present and into the future. In addition to the Meteorological Service of Canada (MSC) weather station, a world-class atmospheric research facility was established near Eureka in 1993 initially as the Arctic Stratospheric Ozone Laboratory (ASTRO). In 2005, the facility became a continuously operating research station, under the name Polar Environment Atmospheric Research Laboratory (PEARL) which relies on the facilities at Eureka for life support and other infrastructure needs. The work of so many people who have done so much to conduct the important atmospheric work at Eureka is an inspiration to make sure this station celebrates its 100th birthday and beyond.

About the Author

John served from 1956 to 1958 as a Radio Operator and meteorological observer at Resolute Bay and Eureka, Nunavut. He followed a career in telecommunications and information technology and was the Executive Secretary of the 1984 Worldwide Commission on Telecommunications under the auspices of the International Telecommunication Union, like WMO, a UN specialized agency. He retired from the Government of Canada as Director General, Government Telecommunications Agency. He has been associated for many years with UNESCO. He has maintained a life-long interest in telecommunications and meteorology the High Arctic and has compiled a collection of photographs, documents and stories about the Joint Arctic Weather Stations: 1947-72. John is a CMOS member.

Andrew Thomson, Eureka Weather Station, John Gilbert, Jud Courtney, Per Stoen