Science de l’océan, navires et souveraineté

– Par Douglas W.R. Wallace –

La mise hors service soudaine, mais pas inattendue en janvier 2022, du navire de recherche de la Garde côtière canadienne NGCC Hudson, sur la côte est, après une longue série de pannes et de réparations, aurait dû être un signal d’alarme pour la communauté de la recherche océanographique du Canada. Le Hudson avait 59 ans, avait servi dignement des générations de scientifiques canadiens et était, au moment de sa disparition, l’un des plus anciens navires de recherche océanique au monde, sinon le plus ancien.

Le fait que la recherche canadienne essentielle sur le climat et la biodiversité marine le long de la côte est du Canada dépende d’un actif aussi vénérable, mais vulnérable est la conséquence de décennies de décisions différées et, surtout, de l’absence d’un débat national ouvert sur les besoins et les stratégies de remplacement de la flotte.

En conséquence, les programmes de recherche et de surveillance gouvernementaux et non gouvernementaux ainsi que les chercheurs au Canada continuent de lutter pour prendre la mer et le débat national est toujours nécessaire. Cette situation survient à un moment où les changements climatiques et les autres menaces qui pèsent sur l’océan s’accélèrent et où le besoin de connaissances sur l’évolution des conditions le long de nos côtes et en haute mer se fait de plus en plus sentir. La question est multigénérationnelle et entraîne des répercussions sur l’avenir : les chercheurs canadiens en début de carrière, en particulier, sont désavantagés par rapport à leurs pairs d’autres pays, car ils n’ont pas accès au temps passé en mer sur des navires où ils peuvent apprendre les uns des autres et développer des compétences et des réseaux de leadership. Les ministères du gouvernement fédéral, en particulier, se sont efforcés de trouver des solutions à court terme et, dans de nombreux cas, de réduire, de retarder et de reporter les programmes de recherche.

La « solution rapide » consistant à affréter des navires étrangers pour soutenir la recherche au large des côtes canadiennes semble, à première vue, judicieuse. Après tout, le partage et la coordination des infrastructures internationales sont utiles et devraient être la norme, en particulier dans le domaine de l’océanographie. Le « partage » international des navires, en tant que solution à la crise de capacité du Canada, pourrait donc être perçu de manière positive. Toutefois, la valeur et les avantages du partage et de la coordination dans le domaine de l’océanographie reposent généralement sur des principes de réciprocité, plutôt que de dépendance. En raison du manque de capacité canadienne, les solutions « rapides » qui consistent à affréter des navires étrangers ne peuvent être considérées comme des exemples de collaboration ou de partage et sont plutôt basées sur la dépendance.

La situation n’a pas besoin d’être aussi grave, et des solutions créatives existent, même en l’absence de construction de multiples navires de recherche neufs, très coûteux et hautement personnalisés. Ces solutions sont discutées au sein d’un groupe de travail national sur les navires de recherche qui a été mis en place pour soutenir une discussion nationale sur l’infrastructure des navires de recherche. Les solutions de rechange comprennent des accords créatifs d’affrètement de navires avec d’autres pays (par exemple, en s’appuyant sur le partage du temps sur le brise-glace de recherche canadien NGCC Amundsen) et la création d’un nouveau système national d’« infrastructure modulaire de recherche océanique interopérable ». Ce dernier permet de convertir temporairement des navires canadiens non spécialisés de divers types en plates-formes de recherche sophistiquées. La capacité des nouveaux navires du secteur privé se développe également rapidement et pourrait offrir de nouvelles plates-formes construites pour une utilisation flexible lorsqu’elles sont conçues pour accueillir des infrastructures de recherche modulaires construites au Canada.

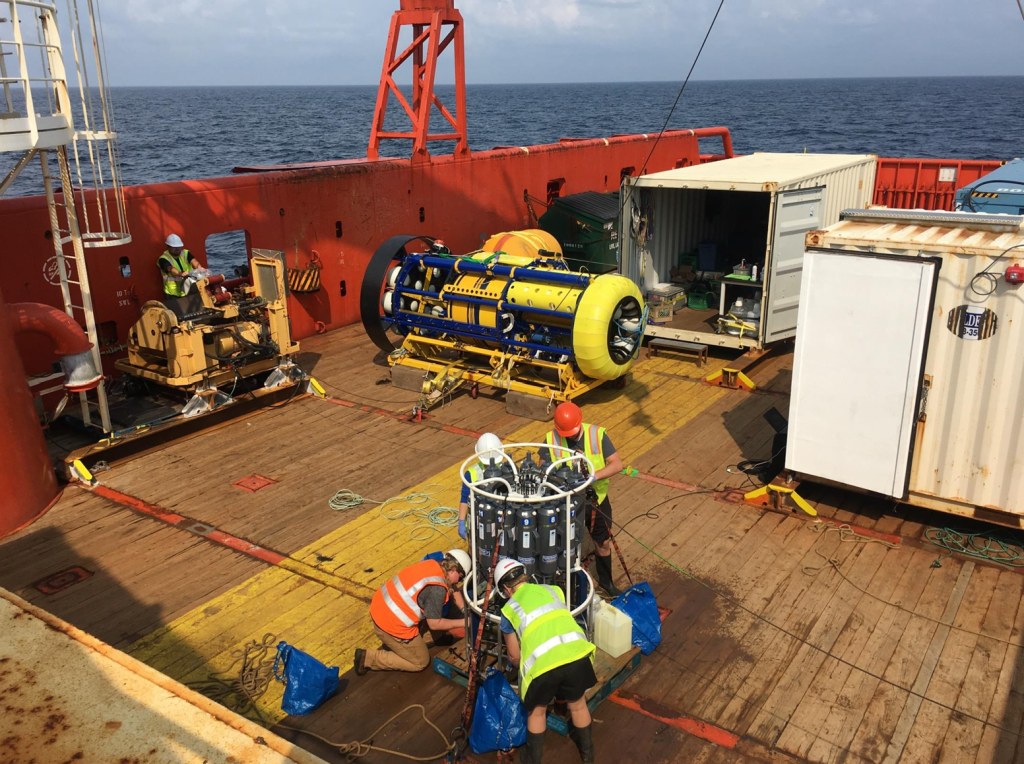

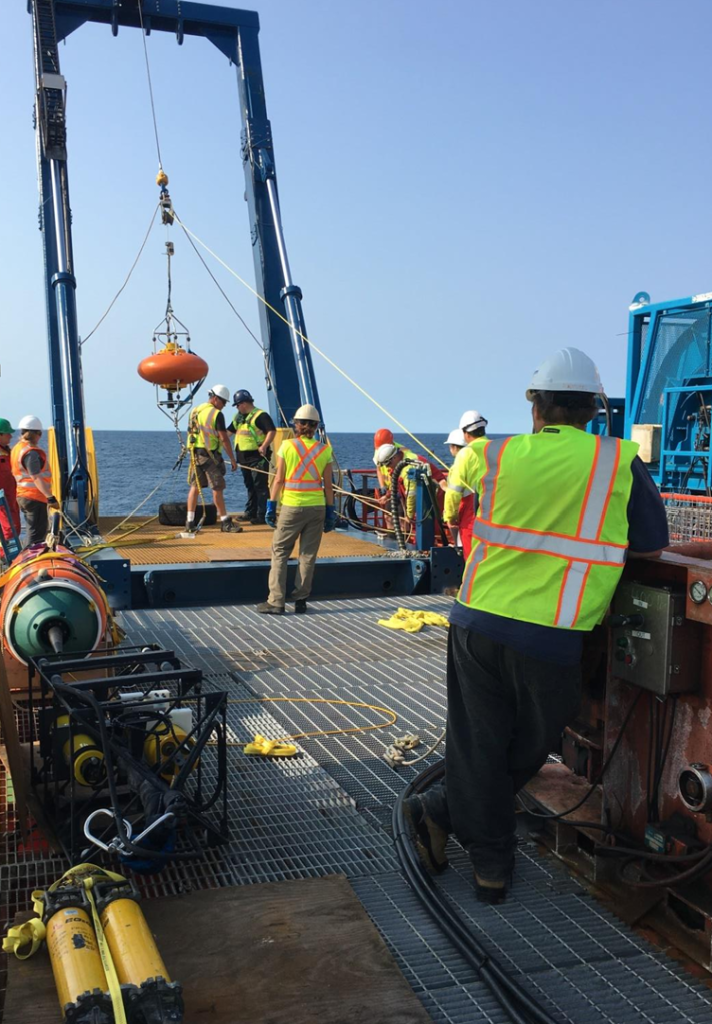

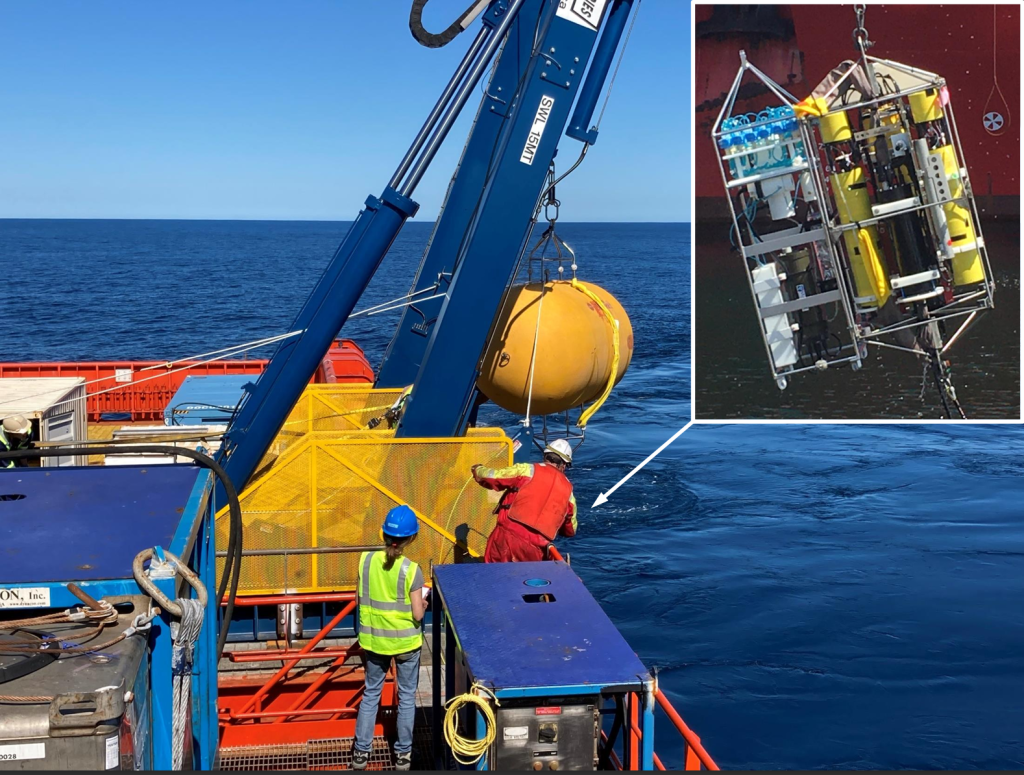

Ces idées et solutions émergent et sont discutées en grande partie dans les secteurs universitaires, sans but lucratif et privé. Actuellement, la valeur de l’infrastructure modulaire est démontrée dans le cadre d’une collaboration innovante entre la Marine royale canadienne (MRC), les ministères scientifiques du gouvernement et les universités pour mener la première expédition de recherche canadienne en Antarctique. L’un des navires de patrouille extracôtiers et de l’Arctique (NPEA) de la MRC a été équipé d’une infrastructure de recherche conteneurisée afin de permettre la réalisation d’un programme de recherche avancée sur un navire qui n’a pas été conçu pour la science. De même, l’utilisation de ces infrastructures pour soutenir la recherche à partir de navires commerciaux tels que les navires ravitailleurs de plate-forme au large a été démontrée.

Le gouvernement fédéral devrait maintenant participer et soutenir un débat national ouvert, y compris sur les options, notamment en envisageant des partenariats public-privé-sans but lucratif au Canada, entre autres avec des organisations autochtones, qui peuvent répondre aux besoins étendus et croissants en matière d’accès scientifique à l’océan. Cela devrait inclure la conception, l’acquisition et l’équipement de nouveaux navires flexibles, polyvalents, à émissions faibles ou nulles, construits pour s’adapter à l’infrastructure modulaire construite par les fournisseurs canadiens de technologies océaniques. En particulier en cette période d’inquiétude concernant la souveraineté canadienne, il est essentiel de réduire la dépendance à l’égard des navires et de la bonne volonté d’autres nations et d’investir dans des solutions canadiennes élaborées conjointement qui répondront aux besoins essentiels de la recherche océanique, tant pour les chercheurs gouvernementaux que pour les chercheurs non gouvernementaux.

– By Douglas W.R. Wallace –

The sudden, but not unexpected, decommissioning in January 2022, of the Canadian Coast Guard’s East Coast research vessel CCGS Hudson, following a long series of breakdowns and repairs, should have been a wake-up call for Canada’s ocean research community. The Hudson was 59 years old, had served generations of Canadian science worthily and was, by the time of its demise, amongst the very oldest ocean-going research vessels in the world, if not the oldest.

The sudden, but not unexpected, decommissioning in January 2022, of the Canadian Coast Guard’s East Coast research vessel CCGS Hudson, following a long series of breakdowns and repairs, should have been a wake-up call for Canada’s ocean research community. The Hudson was 59 years old, had served generations of Canadian science worthily and was, by the time of its demise, amongst the very oldest ocean-going research vessels in the world, if not the oldest.

That critical Canadian research on climate and marine biodiversity along Canada’s east coast relied on such a venerable but vulnerable asset was the consequence of decades of deferred decisions and, most of all, lack of an open, national discussion about needs and strategies for fleet replacement.

The subsequent and continuing situation is that both government and non-government research and monitoring programs and researchers in Canada continue to struggle to get to sea and the national discussion is still needed. This at a time when climate change and other threats to the ocean are accelerating and the need for knowledge about changing conditions along our coasts and in the open ocean is growing. The issue is multi-generational and impacts the future: Canadian early career researchers, especially, are disadvantaged in relation to their peers in other nations in lacking access to sea-time on vessels where they can learn from each other and build leadership skills and networks. Federal government departments, especially, have been scrambling for short-term fixes and in many cases reducing, delaying and deferring research programs.

Short-term “fixes” implemented within Federal departments, particularly by Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) Canada have included chartering of research vessels from foreign institutions. For example, DFO spent $5 million to charter a vessel (RV Atlantis) from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, USA to conduct time-critical work along Canada’s East Coast following Hudson’s decommissioning. The UK research vessels RRS James Cook and RRS Discovery have been chartered from the UK’s National Oceanographic Centre, again to conduct work off Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. This included mapping and geological sampling of the Canadian seafloor off Nova Scotia for Natural Resources Canada. Such research is of major importance for Canada, including for development of offshore wind power resources. This year, key monitoring is likely to take place on French and US vessels.

Short-term “fixes” implemented within Federal departments, particularly by Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) Canada have included chartering of research vessels from foreign institutions. For example, DFO spent $5 million to charter a vessel (RV Atlantis) from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, USA to conduct time-critical work along Canada’s East Coast following Hudson’s decommissioning. The UK research vessels RRS James Cook and RRS Discovery have been chartered from the UK’s National Oceanographic Centre, again to conduct work off Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. This included mapping and geological sampling of the Canadian seafloor off Nova Scotia for Natural Resources Canada. Such research is of major importance for Canada, including for development of offshore wind power resources. This year, key monitoring is likely to take place on French and US vessels.

The arrangement for the RV Atlantis included a collaboration with US scientists who would use specialized equipment to collect data in Canadian waters and share it with DFO. The timing was fortuitous: the vessel was available at short notice due to repair work being done to the famous research submersible, “Alvin”. In another year, the vessel might not have been available.

These short-term arrangements are entered into, as are many decisions about research vessel infrastructure, without broad discussion about the overall needs of Canadian researchers including of early career researchers.

The CCGS Naalak Nappaaluk, the costly ($1.28 billion) replacement for the Hudson, was launched in August 2024 after much delay, and could enter service in 2025. However it will not meet the growing demand for information about the ocean on its own and the continued dependency on foreign institutions and their vessels for access to Canadian waters on the East coast is likely to persist. This dependency has been the situation facing Canada’s academic researchers for 2-3 decades, as the Canadian-operated research fleet, which was able to meet needs of that community in the 1980’s and 1990’s, has shrunk steadily in size, aged and suffered from reduced reliability. For example, ocean researchers from universities such as Dalhousie have come to rely on access to German or Irish vessels to conduct research off the east coast. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this access was shut off, stranding Canadians ashore and demonstrating the downsides of dependency. In 2022, a large team of researchers from Dalhousie and Memorial University of Newfoundland, had to fly and transport all of their equipment to Galway, Ireland in order to embark on an Irish research vessel. This vessel then sailed 5400 kms back and forth across the Atlantic Ocean to reach its intended working area in the Labrador Sea off Canada’s east coast. The equivalent transit from/to St. John’s, Newfoundland would have been about 2000 kms. These are examples of the inefficiencies and increased carbon emissions that use of foreign vessels forces on Canadian researchers

A similar problem is developing on the West Coast, where the one remaining Canadian Coast Guard vessel (CCGS Tully) is in high demand and approaching the end of its life with no clear plan for replacement. Only in northern regions is the situation for multidisciplinary ocean research in Canada’s offshore waters functioning. Arctic ocean research benefits from an innovative cooperation between the Canadian Coast Guard and a University-based not-for-profit organization that shares responsibility for operating Canada’s research icebreaker, the CCGS Amundsen.

The ”quick-fix” of chartering foreign vessels to support research in Canada’s offshore appears, at first glance, to be sensible. After all, international infrastructure sharing and coordination is valuable and should be the norm, especially, for ocean science. International “sharing” of vessels, as a solution to Canada’s capacity crisis, could therefore be viewed in a positive light. However the value and benefits of sharing and coordination in ocean science are based typically on principles of reciprocity, rather than dependency. As a result of the lack of Canadian capacity, “quick-fix” solutions that involve chartering foreign vessels cannot be considered to be examples of collaboration or sharing and are, rather, based on dependency.

Reliance on charters of foreign research vessels has a number of other disadvantages for Canada, including:

- Ocean research is often time-critical, due to seasonal changes in ecosystems and, of course, weather. There are no guarantees that Canada will be able to access foreign vessel capacity at required “peak” times of year or when it is needed. There is a risk of obtaining access to vessel time when no-one else needs or wants it.

- Cost and CO2 Use of foreign vessels generally means extra costs and emissions as, typically, it involves long transits, sometimes across entire ocean basins. Moving a research vessel to/from Europe involves transits of thousands of kms which at current prices costs several hundred thousand dollars in fuel alone. The associated extra CO2 emissions with conventional research vessels are very significant.

- Lack of access to vessel time. To-date, charters of foreign vessels have been negotiated on an individual basis for a specific organisation’s own purposes. There is no mechanism within Canada to coordinate such charters so that use of the vessels can be maximized for the benefit of all Canadians. To date, there has been no consultation by government science based organizations with Canadian, non-government researchers as to their needs, or whether there would be interest in accessing additional days of vessel time during a contract for other research needs. Given the high cost of even the required transits, this risks inefficient use of valuable research funds.

- Lack of opportunity for Canadian Early Career Researchers. The lack of national discussion about vessel access neglects the needs of early career ocean researchers as well as students at Universities and colleges across Canada. In contrast to their peers in other countries, Canadian early career researchers generally lack access to vessel time and rarely, if ever, have the opportunity to plan or lead expeditions. (Notable exceptions are, again, the University-associated vessel operations of Amundsen Science (for Arctic research) and Reformar (for research in the Gulf of St. Lawrence). This limits the development of Canada’s future human capacity for research.

- Sovereignty: research vessels are used to investigate conditions and collect data from within Canada’s Exclusive Economic Zone and Territorial Waters that is of high-value for development and management of Canada’s resources (living and non-living), planning of energy infrastructure, and collection of data of importance for negotiating climate change and biodiversity agreements, etc. In an era of growing concern over Canadian sovereignty, dependence on foreign vessels is, very clearly, problematic. (It would, for example, be almost inconceivable for government-supported research in the EEZ of the USA to be dependent on use of foreign vessels).

- Lack of strategic investment. Most significantly, sending funds out of Canada for charters of foreign vessels does nothing to improve the situation within Canada, for Canadians. Unfortunately, the practice risks perpetuating dependency. Further, the research vessels that are being chartered have traditional propulsion systems, i.e., they burn heavy oil. The same institutions that are accepting charters from Canada are currently planning for a transition to vessels of the future that will use low-carbon alternative fuels and that are more efficient. Industry is also moving fast in that direction. Funds spent on chartering foreign vessels built in a different era are not available to be used to advance the innovative, forward-looking, low-emission solutions for the future.

The situation does not need to be so dire, and creative solutions are available, even in the absence of building multiple, new, very expensive, highly-customized research vessels. These solutions are being discussed within a National Research Vessel Task Team that was set up to support a national discussion about research vessel infrastructure. Alternatives include creative vessel-bartering arrangements with other countries (e.g. building on sharing of time on Canada’s research breaker CCGS Amundsen) and development of a new, national system of interoperable “Modular Ocean Research Infrastructure”. The latter allows for temporary conversion of non-specialized Canadian vessels of various types into sophisticated research platforms. New, private sector vessel capacity is also developing, rapidly and could offer new platforms built for flexible use when designed to accommodate Canadian-built modular research infrastructure.

The situation does not need to be so dire, and creative solutions are available, even in the absence of building multiple, new, very expensive, highly-customized research vessels. These solutions are being discussed within a National Research Vessel Task Team that was set up to support a national discussion about research vessel infrastructure. Alternatives include creative vessel-bartering arrangements with other countries (e.g. building on sharing of time on Canada’s research breaker CCGS Amundsen) and development of a new, national system of interoperable “Modular Ocean Research Infrastructure”. The latter allows for temporary conversion of non-specialized Canadian vessels of various types into sophisticated research platforms. New, private sector vessel capacity is also developing, rapidly and could offer new platforms built for flexible use when designed to accommodate Canadian-built modular research infrastructure.

These ideas and solutions are emerging and being discussed largely within the academic, not-for-profit and private sectors. The value of Modular Infrastructure is being demonstrated within a ground-breaking collaboration between the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN), Government science departments and academia who together conducted the first Canadian research expedition to Antarctica. One of the RCN’s Arctic and Offshore Patrol Vessels (AOPVs) has been equipped with containerized research infrastructure to allow an advanced research program to be conducted on a vessel that was not designed for science. Similarly, use of such infrastructure to support research from commercial vessels such as offshore Platform Supple Vessels has been demonstrated.

The Federal government should now join in and support an open, national discussion, including of options, including consideration of public-private-not-for-profit partnerships within Canada, including with Indigenous organisations, that can address the broad and growing needs for science access to the ocean. This should include design, acquisition and outfitting of new, flexible, multi-purpose, low or zero emission vessels built to accommodate modular infrastructure built by Canadian ocean tech providers. Especially in this time of concern about Canadian sovereignty it is critical to reduce dependency on vessels and goodwill of other nations and invest in co-developed, Canadian solutions that will support the critical ocean research needs. of both government and non-government researchers alike.